D. J. Hinman; Talad in Southeast Asia ICHIBA アジア市場を探歩する; Tosei-sha Co. Ltd.; Tokyo; 2021

Available in the U.S. from itascabooks.com and Amazon; available in Japan from the publisher tosei_sha.jp

Photographer’s Statement

The way of marketing food products to consumers differs widely among various cultures, from home-grown produce, to farmers’ markets, to industrial farming and supermarkets and, now in the digital age, to on-line sales. This series of black-and-white photographs explores the neighborhood markets (talad in Thai language or ichiba in Japanese) in Southeast Asia and elsewhere in East Asia. Imagine if you will a world where goods are sold directly from vendor to customer. Everything is done by hand – no PCs or other digital gimmicks here. Sometimes the cash register is a basket suspended on a spring rope. The buyers and sellers negotiate the prices. Produce is weighed by hand on a double-arm balance. From the viewpoint of a Westerner who has lived in modern cities such as New York and Tokyo, I was astonished to find such open-air morning markets and night markets, first in Bangkok and subsequently throughout the region, both in large cities and small villages. This series, “Talad in Southeast Asia,” covers nine countries in Southeast and East Asia over a period of 11 years, and has been the theme of two solo photography exhibits in Tokyo.

The series progressed through three phases as I explored these markets. I think that the products were the most curious part for me at first. Fruits and vegetables of various shapes, colors and textures that I had never seen before. Many varieties of rice and other grains, displayed in bulging burlap bags sitting on the floor. A wide variety of meats, including live animals such as chickens, fish and snakes. The variety seemed endless.

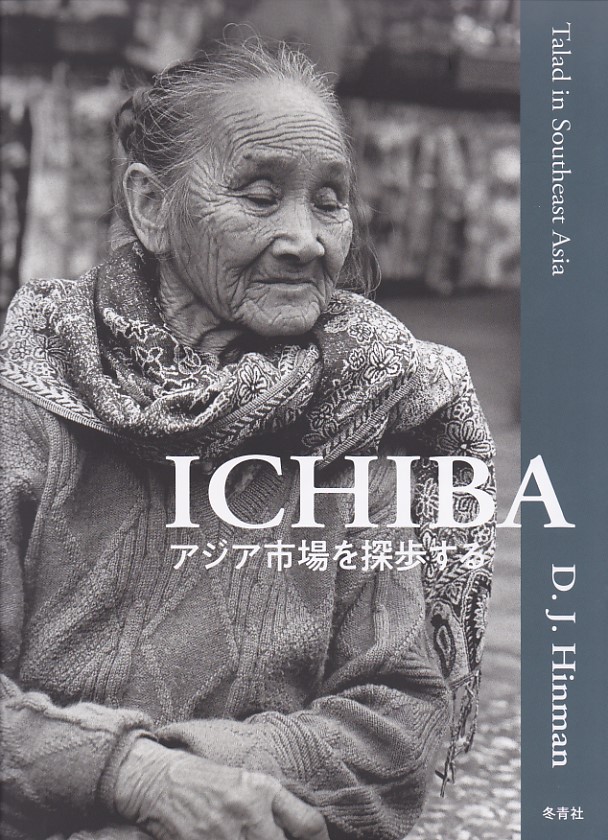

The next phase of my exploration was the interactions between vendors and their customers. The exchanges were face to face, and hand to hand. Not only were the exchanges directly between vendor and customer, but often they were between neighbors. The pace was slower and people took the time to chat with one another. The markets (talad) form a social community as well as a commercial enterprise. The third phase centered on the people themselves, which for me as a photographer was the most rewarding. Older people and younger people, women and men, sometimes even children, their faces carried their life stories. Moreover, these were people going about their usual daily lives. I have come to realize that such markets retain an intangible element of social community that, unfortunately, too often has been lost in our so-called developed world.

As an added advantage for my style of photography, in the markets I was anonymous and could become almost invisible. Usually I mostly just watched. Sometimes the people reacted to me, usually in a friendly way, and sometimes they ignored me; they generally acceded to my request to take their photograph. I tried to become invisible to capture people as they really were, as they went about their daily business. My goal for this series is to create a window into the life of these talad, focusing on the people there as well as the social communities. During the series, I experienced an unaccustomed sense about the markets and their people, almost a sort of nostalgia. Perhaps this series of photographs will portray the spirit of the talad while they still exist.

To see more of the contents of Talad in Southeast Asia, go to the gallery.

For a narrative about the photographs, go to the Monochrome Chronicle #09.