The previous issue of The Monochrome Chronicles focused on the salaryman experience from the viewpoint of Tokyo’s Yamanote Line. This issue narrows the focus down to a single stop in the line known as Ikebukuro Station.

Of the 30 stops on the Yamanote Line as it loops around central Tokyo, Ikebukuro Station especially attracted the attention of my camera, possibly because of the diversity of passengers at this station. Such a mix of passengers travels through Ikebukuro: young and old, blue collar and white collar, rich and poor. Ikebukuro is the transfer station for several commuter lines so many office workers change trains there. Several universities are nearby so many students use this station. Architecturally, the station is rather pedestrian but it is the third largest station in Tokyo with ridership of almost 3 million passengers each day and yet, though the odds were about one-in-a-million against me, I have been able to focus on salarymen as individuals.

In Japan, the trains stop running at 1:00 AM and then start again at about 5:30 AM the next morning. Salarymen often go to an izakaya after work before going home. Usually they would go to the izakaya in groups but often they would have to find their way home alone. Around 1:00 AM on Friday nights Ikebukuro Station would be invaded by crowds of salarymen rushing to catch the last train home. Over the course of 2 years, I frequently went to Ikebukuro Station around midnight on Friday nights to photograph the goings-on there, returning to my home station in Ebisu by the last train.

Waiting there for the transfer train, the events of the week finally caught up with him. The drama in this image is heightened by the low camera angle and the extensive vacant space in the foreground.

Some guys only get as far as the platform, waiting for the last train. Some of them pass out while waiting. This guy looked so relaxed, like he had just laid down for a nap. Where were his friends?

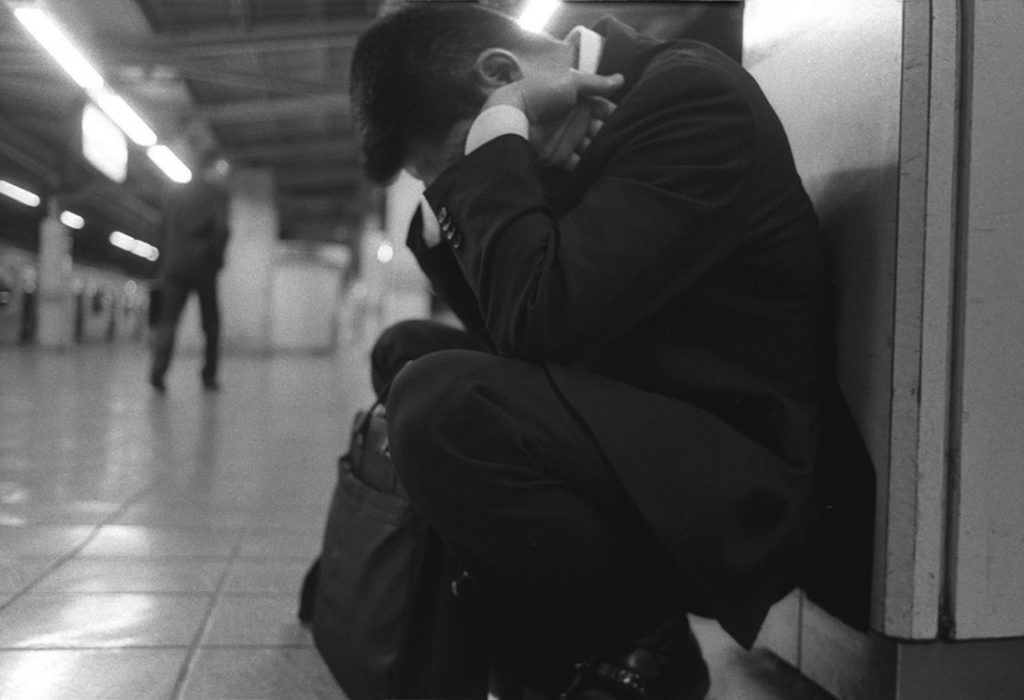

Clearly the crouching salaryman is the central focus of this image, yet he seems to be so small compared to the rest of the composition, which magnifies the feeling of isolation. I don’t know the details of the story, nor did I wait to see the outcome. I am just an observer and I leave the rest up to the viewer’s imagination.

Many things are happening in this image, though at first glance it may seem to be somewhat static. That well-worn briefcase probably would have many stories to tell if it could. Its owner had been carrying it for a long time so he must have been sentimentally attached to it. And the man himself, seemingly just standing on the platform, actually wasn’t just standing, he was on his way home. He was wearing the salaryman’s regulation black suit and black shoes, and he was carrying is overcoat over his arm, so presumably the weather was clement. The train rushing past on the adjacent track adds another element of motion. Another weary Friday night on the platform of Ikebukuro Station.

Symbolically, this image represents the end of Friday night in Ikebukuro Station.

The next scene would be Ikebukuro Station on Saturday morning.

The platforms would be awash with salarymen either hungover from the night before, or still drunk or in an alcoholic stupor. How long would they stay there before waking up? One man’s briefcase sat beside him, unmolested. Tokyo is so safe. Obviously, they were waiting on the platforms for the first train, waiting to go home. They still wore their salaryman uniforms, so where had they been? Like these two, most of them would be young guys. Their hangovers must have been painful.

This is the flip side of the last train on Friday night. After staying out all night, probably with colleagues, the salaryman has to wait until the first train on Saturday morning. This is such a common sight on Saturday morning in Tokyo.

Let me deviate for a while from the salaryman series. As I wrote in the introduction to this episode, Ikebukuro Station attracted my attention in part due to the diversity of passengers who traverse through the station.

The mood of the first train on Saturday morning is reflected in this image, I think. Inside, the cars are remarkably quiet – even more quiet than usual (trains in Japan generally are quiet). In this extreme close-up taken from an unconventional angle over the subject’s shoulder, this rider seems to be deep in thought. This impression is heightened by the soft focus and the narrow range of grays in the palette. Granted, it is a lucky, shot-from-the-hip image (or literally shot from the chest), the outcome effectively portrays the somber moment.

Returning to Ikebukuro Station at the time of the first train, this image permits several levels of interpretation. At first, I assumed that this man was a drunken, or hung-over, salaryman who had been out all night. His clothes – casual T-shirt and jeans – belie that interpretation, though. Something is amiss. Another element of the picture is the people walking past, seemingly oblivious to the man’s plight. The indifference of the strangers is well-recognized, of course, and not unique to Tokyo. Somehow it seems more poignant in this photograph. Then again, after taking a few frames, I too passed on so who am I to judge? I reverted to the hardened, jaded New Yorker who can walk the streets and not see the people around him.

In a departure from the main theme of this episode, let me note that a wide cross-section of Japanese society passes through the station on any given day. Even the toilets convey their own stories. I hesitated before taking this shot but eventually my little voice overcame my inhibitions. The result is a juxtaposition of an ordinary occurrence with an almost surreal drama. To say more would be to detract from the impact of the image.

As further illustration of he diversity of the passengers in Ikebukuro Station, well, I suppose I need to explain a bit of background to this image. This man was wearing what are known as “neekabaka pantsu” – the Japanification of “knickerbocker pants.” Many construction workers and other hard-hat laborers wear them as a safety precaution.

Getting back to the photograph per se, the aesthetics of the entire composition is the key element, I think. The interplay between the almost graceful curves of the man’s uniform and the harsh geometry of the floor of the platform enlivens the image, while the train in the backgrounds sets the context. The soft lighting and the high-key palette create a soothing mood. The outcome is a pleasing counter-point to the rest of the images in this episode, I think.

Ikebukuro Station, then, became one of the focal points of a new series for me, a further exploration of the so-called salaryman culture in Tokyo. I went frequently to Ikebukuro Station, sometimes staying for an hour or more just waiting, observing, and photographing the salarymen as they passed through the station on their way home. One night I stayed so long on the platform that one of the station attendants came over to me to see whether I was OK. Did I need help? In fact, all he said was, “Daijobu desu ka” (literally, “Is it OK?”) but in typical Japanese-style communication, his question went much deeper. I replied simply, “I’m OK,” and he seemed satisfied with this answer.

This episode of The Monochrome Chronicles, along with the previous one, covers some of the highlights of my series on the Japanese salaryman. Nearly 13 years have passed since I finished this series so writing about it at this time is a little strange. Looking at the photographs triggers my memory. I remember clearly the moment I tripped the shutter for many of them. Now, however, my point of view about the series has changed. I suppose I see the series more objectively through the retrospectroscope.

The experience of creating such a long-term series influenced other features of my photography. It opened my eyes to the realization that photography can be a means of exploration. So many aspects of the salaryman culture were unknown to me at the start. Curiosity, and the urging of my little inner voice, drove me forward. This, coupled with an appreciation for imagination, paved the way for future long-term series – which will feature in future episodes of The Monochrome Chronicles.