This episode of The Monochrome Chronicles investigates a part of Japanese culture that is, in my opinion, unique to Japan: the salaryman. I spent about 4 years developing this series, which ultimately lead to three solo exhibits in 2007-2009 here in Tokyo. The salaryman experience is both deep and wide, too extensive to fit all of it into the viewfinder of my camera. With the caveat that my series covers only a small segment of the salaryman’s life, this episode and the next one show some of my impressions. My point of view is unique in the sense that I was both outsider and insider in the salaryman world, an outsider by virtue of being non-Japanese (or “gaijin”) and an insider by working for more than 20 years among many salarymen for a large Japanese company and being considered by some to be an honorary salaryman.

My salaryman series emerged gradually. I started by exploring the life of the salaryman on the Yamanote Line train. This train line circumnavigates central Tokyo’s business, shopping and entertainment districts. The series encompassed several phases of the salaryman’s life: the morning commute, the drinking parties after work and going home on the last train on Friday night, or if they missed the last train then the first train on Saturday morning.

A stereotype of the Japanese salaryman would be a middle-aged married company employee, who wears a black suit, white shirt and dark tie as a sort of uniform, and who works arduously long hours at a desk in his office. In time, I came to realize that what distinguishes a Japanese salaryman from a western businessman is the level of commitment to his company. He views the company as a community and his co-workers as an extended family. A salaryman works for the company whereas a businessman works for his salary.

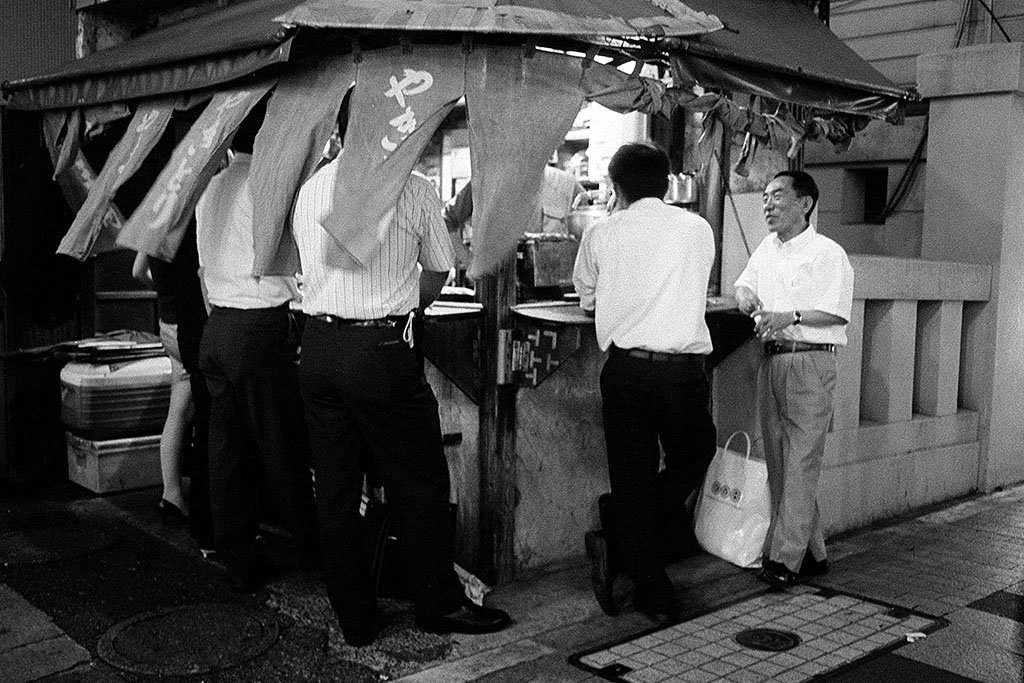

One of my starting points was a neighborhood in Tokyo called Shimbashi, a nucleus for salaryman culture. Many companies are located in the neighborhood and salarymen are drawn there to work. Shimbashi also has many casual restaurants – known as “izakaya” –ramen shops, bars and so on that cater to the after-hours crowd. Often co-workers go in small groups to an izakaya after work and before going home. This is called “nomikai” in Japanese, a contraction of the words “nomimasu” (to drink) and “kaigi” (a meeting), an essential element of salaryman culture.

A salaryman’s day starts with a commute to the office by train during the morning rush hour. (This series was well before the COVID-19 era and the days of teleworking from home.) In Tokyo, the commute often takes an hour or so, and sometimes as long as two hours. The trains are very crowded, as some 40 million passengers use the trains every day.

Commuters spend so much time waiting on the platform for a train to arrive. All is light and shadow above the platform but only shadow and machinery below. The photograph holds few cues about the time of day, so this might be either morning rush hour or evening rush hour.

The harsh fluorescent lighting on the platform transforms the commuters from people into silhouettes. Taken out of context, the image could offer other interpretations, which I’ll leave to the viewer’s imagination.

This doesn’t happen. The platforms are marked to show where the doors will be when the train stops and those waiting stand on either side of the designated spot to allow passengers to get off. Very orderly…and the drivers always stop the trains so that the doors and designated spaces align just right.

In case you are wondering, yes, this image was shot-from-the-hip. And I could find the right vantage point because I knew where the doors would be when the train stopped. Shots like this result from a combination of experience, intuition and luck.

The composition is unconventional, mostly geometric except for the human element. The soft gray pallet creates a soothing atmosphere and the slight blur in the background outside the window adds a hint of motion. All in all, the image seems to contradict the concept of the stress of the salaryman’s world. This is a moment frozen in time.

Turning from the morning rush hour to the opposite end of the salaryman’s day, though typically salarymen work long hours, their day does not end when they leave the office. Often they stop off on their way home at a bar or restaurant with their colleagues from work. Drink flows freely and the conversation becomes uninhibited. For many, this is a means for unleashing the stress that has built up during the work day.

The fare usually is chicken meat but can be almost any part: heart, liver, skin, intestines, uterus (sometimes with an immature egg inside), and so on. Groups of salarymen can stay for a couple of hours munching on yakitori and drinking beer.

Several elements contribute to the depiction of the boisterous mood of this group, such as their body language and gestures, the people and even a bicycle in the background, and the low camera angle. The irregularities of composition – subjects with their feet cut off, slight blur and soft focus, bright lights in the background and the edges – contribute to, rather than distract from, the energy of the photograph.

This image goes far beyond the stereotype of the salaryman, I think. The strong side lighting fortuitously creates a dramatic image of the end of the evening. A street photographer cannot arrange the lighting scheme but must be able to recognize effective lighting when it occurs.

Two shadows moving through a tunnel. This image offers few clues about their identity or their destination. The symmetry is a bit off, contributing to the underlying tension. The time was late Friday night, so maybe they were salarymen either before or after nomikai.

Other interpretations are possible, especially given the lack of detail in the image. It could be a still image from cinema noir. The mood suggests a spy caper in Eastern Europe during the Cold War. Or these might be two gangsters in Chicago during prohibition. In this instance, the lack of detail with the two figures out of focus, which might be critical flaws if this were a documentary photograph, are essential elements in the mood created.

Often, many commuters have to make a mad dash for the last train, especially on Friday night. The lucky ones catch the train. Even those who are lucky enough to catch the train sometimes pass out on the train, so they may or may not get off at their home station. This guy lay sprawled out across three seats in the train. His belt was unbuckled. His shoes were untied. Also, amazingly he had crossed his legs in such an awkward posture. What was behind his dishabille? How would he feel and where would he be when he woke up?

A salaryman sleeping in the seat on the last train on Friday night is a common sight. Sleeping on the floor is a little unusual. This man was flat out on the floor. How did I manage to take this photograph from such a low point of view? By sitting on the floor.

Sleeping on the trains in Tokyo is safe. Some passengers even sleep standing up, leaning against the door or hanging on to a strap handle. This man had dropped his brief case and umbrella, which lay unprotected on the floor. Other passengers boarding the train passed him by. Just another drunken salaryman.

The Yamanote Line trains run in a loop around the city. A full loop takes about an hour. Someone who, like these salarymen, falls asleep may well keep riding around and around the loop until the train makes its final stop. After the train comes to the last stop, the conductors make an inspection tour of the entire train. On Friday night, often they find one or more such sleepers in the car. The train conductor wakes them up and escorts them as far as the platform. After that, the passengers are on their own. Most can make their way through the wicket and out the exit. Others fall asleep again on the platform. Then when it is time to close the station, the security guards wake them up and escort them out the exit. Once again, the passengers are on their own. Usually, singly.

Friday night, the last train at about 1:00AM. From my shooting book: “…A passenger ran past me, toward the rear of the train, and soon he and a trainman ran back in the other direction. The trainman bypassed the passed-out (sleeping) passengers and I knew something was afoot. I followed. Two or three cars away I found the trainman crouched over a salaryman who lay sprawled on the floor. A crowd gathered. The trainman tried vainly to rouse the man.

Soon, about six or eight trainmen…hovered around him, checking for a pulse, loosening his tie. All to no avail, the man lay limp. One passenger readied to give mouth-to-mouth (he’d carried a mouth-to-mouth plastic barrier in his pocket – a physician, or EMT?), then checked for a jugular pulse and found it. Shortly, the man raised his head. He was alive, at least. More officers arrived. In a few minutes, they had him on his feet, supported by about three officers, got him off the train, stood him against a platform pillar. One officer supported him, helping him to stay standing, while the others scurried about collecting the man’s briefcase and glasses, and their equipment. The officer spoke to the man – mostly ‘だいじょぶですか? (Are you OK?)’ – and finally he replied. After a few minutes the man was able to stand unsupported, and walked away. Alone.”

He kept walking. She raised her hand in farewell and called out, “Sayonara.” He turned and replied, “Sayonara.” Again, she called out, “Sayonara” and he replied the same. Finally, as he began descending the stairs, she called, “Saa—yo—naa—raa.” He waved goodnight. Slowly her hand draped over the wall and she laid her head down. He continued down the stairs.

What would happen to those who missed the last train? They could not get home because it was too far to walk and a taxi would be too expensive. These two opted to stay the night in the station.

Inevitably, those who had missed the last train on Friday night would go home on Saturday 07-076-07morning, usually by the first train at around 5:00 or 5:30 AM. For this part of the series, I would sleep at home and get up around 4:30 to catch the first train from Ebisu to Ikebukuro Station. Here is what I found.

Some men would get as far as the train platform on Saturday morning, but then wouldn’t manage to board the train. Someone commented, “It looks like a terrorist attack.” No, just another Saturday morning in Tokyo.

A photograph shows only an instant in time. Now I wonder how long this salaryman lay there before he woke up. How would he then react? After waking up, how long would it have taken him to regain sufficient awareness to take the next step – whatever that might be?

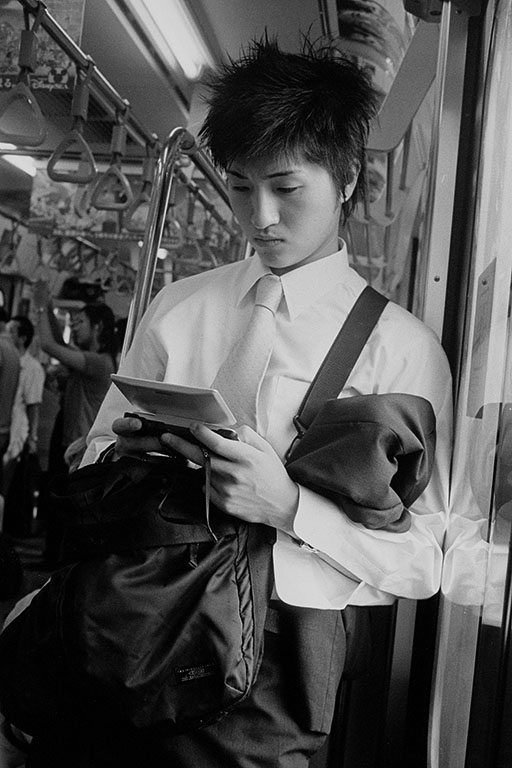

In a sense, this could be a counterpoint to most of the images in this episode. It was Saturday morning, yes, but this guy seems to be on his way to work. Hardly the stereotype of a traditional salaryman and more an icon of a modern-day young salaryman. The unexpected element, though, is his gameboy. To me this image portrays the stage between young-man-just-out-of-university and seasoned salaryman. The soft early-morning sunlight creates a romanticized view of the man’s commute to his office, at least in my imagination.

On the first train on Saturday morning, this woman was very solicitous of her salaryman friend. Probably about 5:30 or 6:00 AM. So early for me, but well…

This image captures a moment of intimacy between the two, but the rest of the story is left to the viewer’s imagination. Had the man been out all night, having missed the last train after nomikai with his colleagues? Other interpretations are possible. The ambiguity here adds to the overall strength of the photograph.

Again, the first train on Saturday morning. This young woman was nearly comatose (either hungover or drunk or, I suspect, she had been drugged), dressed casually and barefoot, with her purse open in front of her.

Typically, other passengers would ignore drunk or hungover passengers, but in this instance they tried to assist her. One man gently slapped her face trying to wake her up. Nothing seemed to arouse her.

Strange, but I don’t remember how the story ended. Were I a photojournalist I might have pursued the story further, but as a street photographer I’m concerned only with the moment, I’m only an observer.

For the final photograph of this episode, let me return to Friday evening.

This image belies much of what the rest of the photographs in this series show. There is no boisterous crowd of fellow salarymen, no crowded rush hour on the train. It is a haunting, melancholic image, I think. It also portrays another side of the salaryman’s life, at least as I’ve observed it. At the end of the day, after all the group meetings and socializing, the salaryman returns home alone.

My salaryman series became one of my major projects in Japan. Over the course of about four years, I spent a lot of shooting time (the time when I feel most alive) on the streets, on the trains and in the train stations, and in the izakaya and nomikai; a lot of time in the darkroom (the most creative time); and a lot of time mounting three solo exhibits (the most stressful times) in a gallery here. This episode of The Monochrome Chronicles has focused on specific aspects of the salaryman’s life on or near the Yamanote Line: commuting by train, nomikai after work, and going home either by the last train on Friday night or, failing that, by the first train on Saturday morning. The next episode will delve into a more restricted milieu, the view of the salaryman from one single train stop, Ikebukuro Station.