In this issue of The Monochrome Chronicles, I turn to another place that occupies a large section of my photographic exploration of Nepal – the village of Khokana. Like Bhaktapur, the people of Khokana are of the Newari ethnic group. In one sense, it is a stopping point in the progression of my series from urban life in Bhaktapur, to life in a village in the Kathmandu Valley and finally to very small mountain villages in the foothills of the Himalayas. And, incidentally, I am sentimentally attached to Khokana as well.

First, let me explain how I first came to visit Khokana. In 2016 I decided to expand the scope of my photography, which until then had focused on Southeast Asia. Nepal became one of my goals. My initial destination was the capital city, Kathmandu, and early one morning my guide called to say we would have to change the itinerary for that day because of heavy rain overnight. Would I consider going to two small villages in the Kathmandu Valley? Well, the time was about 5:00 AM and I was still mostly asleep but I answered, sure, why not?

I had no preconceived expectations about what I would find in Khokana, about an hour’s drive from Kathmandu. A half day of wandering the streets of Khokana and photographing the people there – followed by a 15-minute walk through the hills to the neighboring village of Bungmati – completely captured my photographer’s imagination. I knew that I would return and indeed I returned four years in a row. I’ll let my photographs show why.

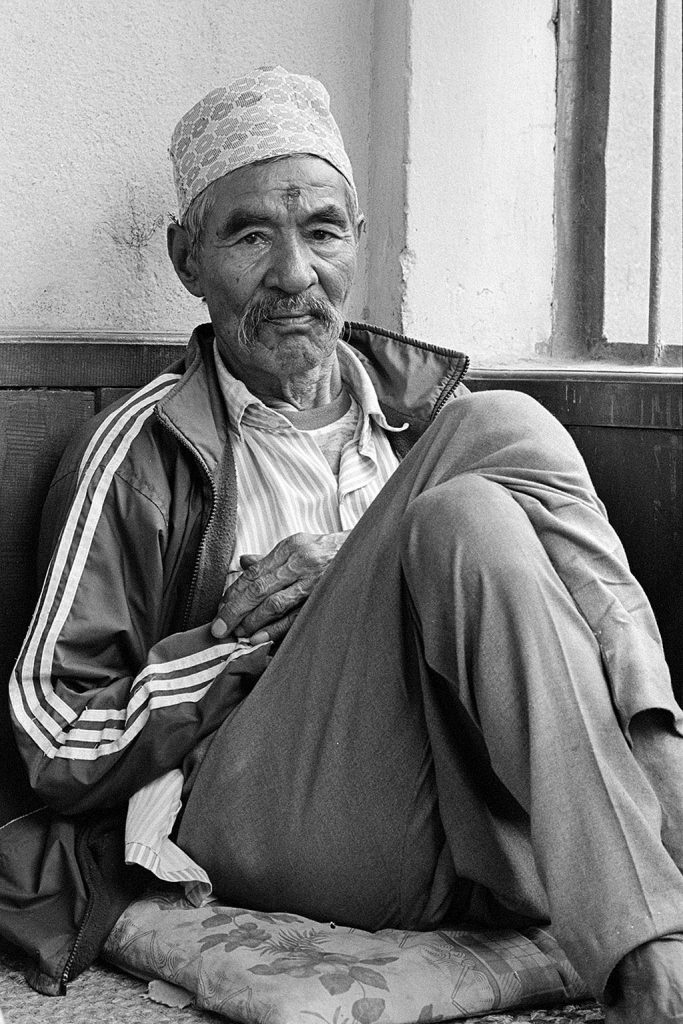

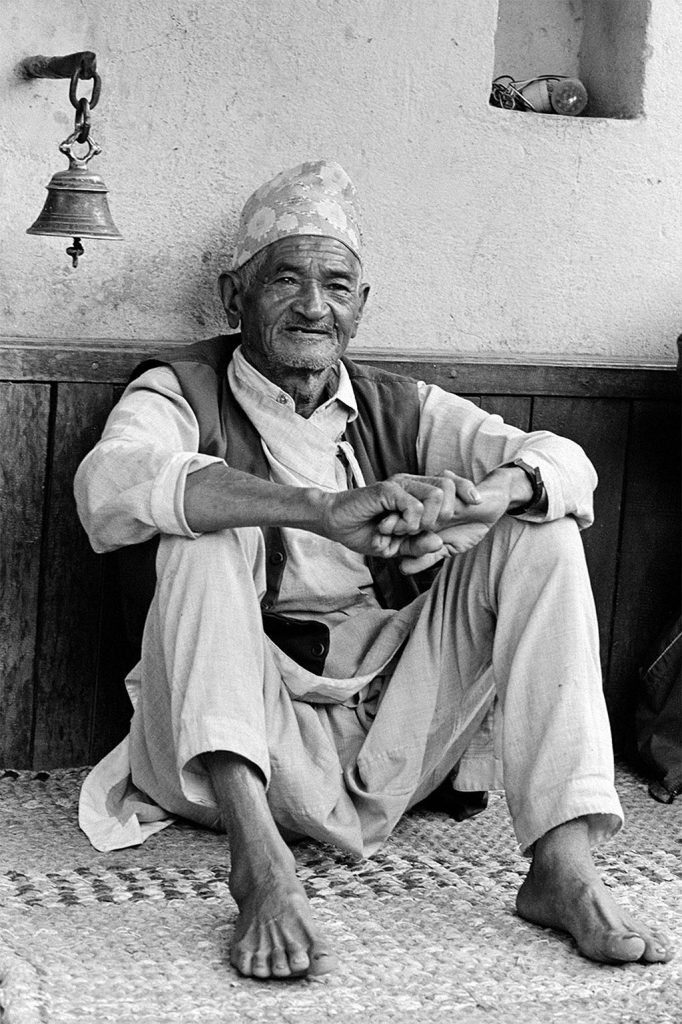

One feature of the local culture is that some public spaces are set aside as social clubs for older men. These are simple rooms, always on a street corner, with bare floors and large open windows. These two men, who were among the first people I met in the village, were sitting and chatting quietly in one such social club.

Although men have their social clubs, women don’t have such designated social spaces but they gather to socialize on the front steps of their homes in the late afternoon.

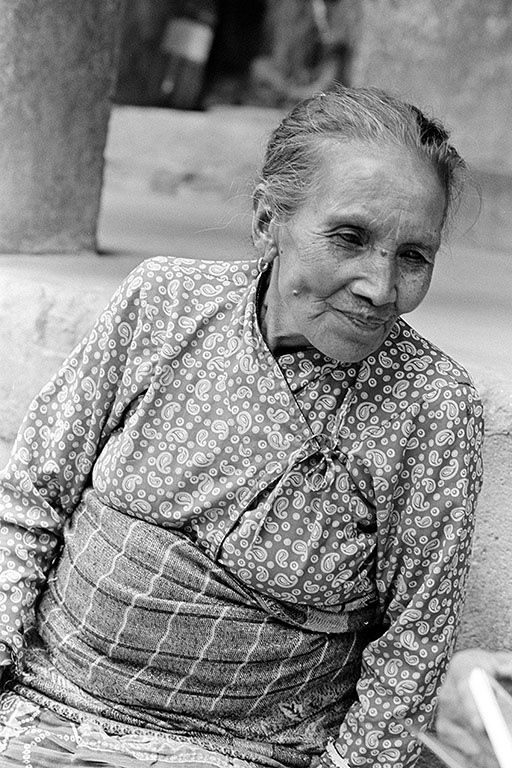

Sometimes I don’t have to do anything, the portrait is just waiting for me and my camera. Though several women were chatting on the steps outside the house, this woman was sitting by herself in an alcove entryway. She was sitting in just this pose when I first saw her. She turned her eyes to look at me briefly, acknowledged my camera, then turned her eyes back into this pose. Well, when I said I didn’t have to do anything, still I had to be ready when my little voice spoke to me.

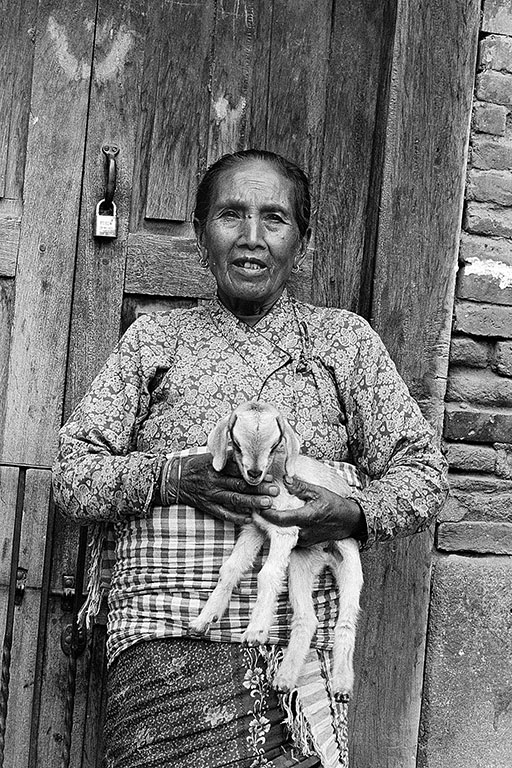

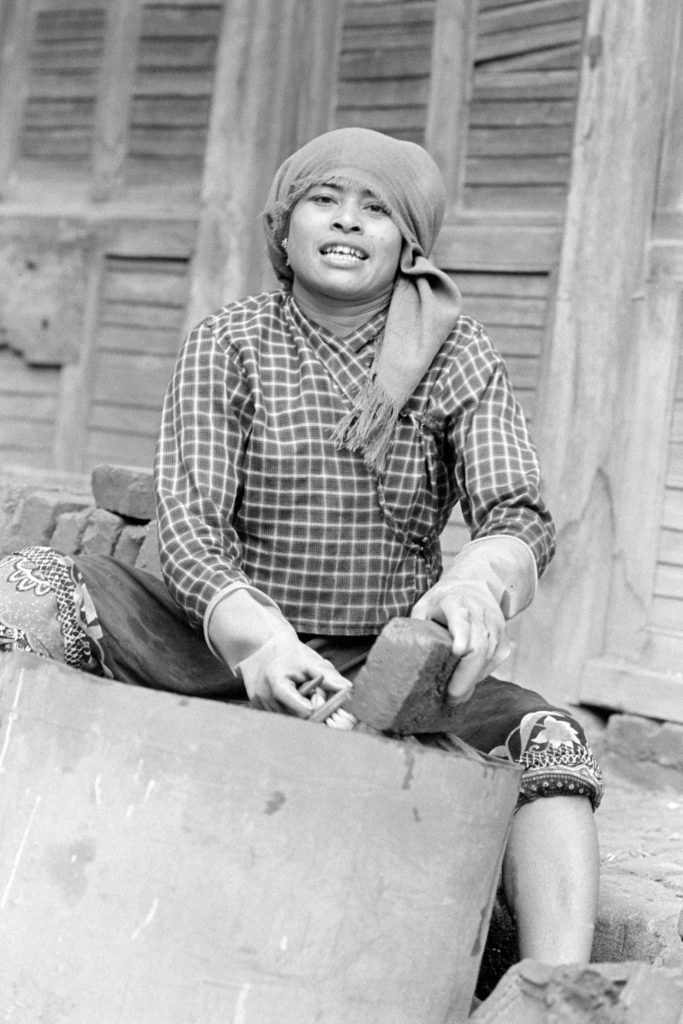

In late afternoon, women in the village gather on each other’s doorsteps, some of them finishing their daily chores and others just socializing. This woman’s friend was spinning yarn on the doorstep. As soon as I saw her, I wanted to photograph this woman, drawn maybe by the striking combination of patterns in the clothes and kerchief she was wearing. She assented to my request for a photograph and at first she was rather awkward but finally she lapsed into this more natural pose.

The composition of this image seems a bit off-kilter. The door in the background obviously is at an angle, but the woman seems to be standing straight. I suspect that this is an illusion. Probably both the door and the woman are at the same angle, but my viewer’s eye wants to make the correction for the woman, a psychological trick.

On my second visit, I brought with me an album of prints from my first visit to show the people in Khokana and to give prints to them. I found one subject and showed her the book. She smiled, and then when she saw her own portrait, she laughed. She called to her neighbors to come and look. Soon a small crowd had gathered, passing my book among themselves.

Each year now I take some prints to give to the villagers. And I take more photographs, of course. Then the villagers say, “Please come back next year to show us more pictures.” By going back year after year I can see how the people age.

A side story. While I was showing the album, one man looked at one of the photographs, turned to the woman standing next to him and said, “He is your husband, isn’t he?” She took another look and then started to laugh. She had not recognized the picture of her own husband.

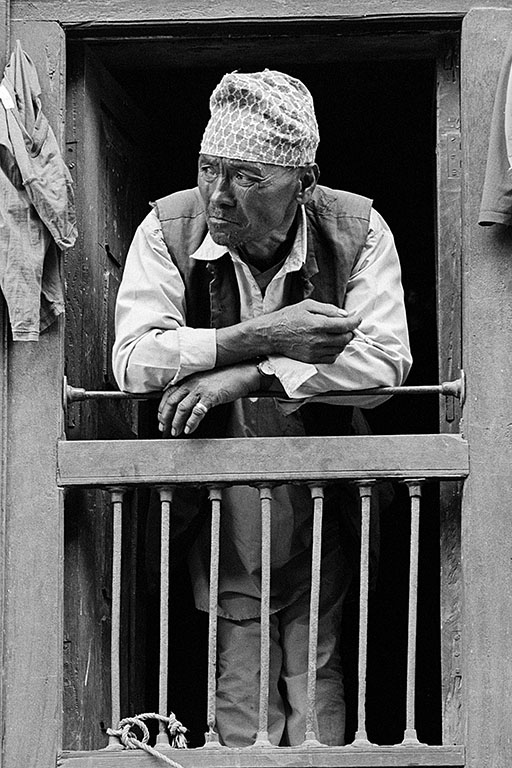

This is the man whose wife did not recognize him in this photograph. I suspect that people in the village are not so accustomed to seeing photographs.

He was watching the goings-on in the street in front of his house. People sitting or standing at an upper floor window is a frequent sight both here in Khokana and in Bhaktapur. Is that a censorious look on his face?

The houses in Khokana intrigue me and one of the villagers volunteered to show me hers. A storage room and toilet occupied the first floor. The second floor contained two sleeping rooms. The only furnishings were pallets on the floor for sleeping. The third floor was one big room for all the activities of daily life. A kitchen was in one corner – only a gas ring stove and a small preparation area. The rest of the room was bare – bare wood floor, bare brick walls, and no furniture. Originally there had been three rooms but the front room and the back room had collapsed in the 2015 earthquake, leaving gaps in the remaining walls that had been closed off temporarily with plastic sheeting. This living space was quite dark even in the middle of the afternoon since there was neither electricity nor windows and the only source of light was daylight filtering through the plastic sheeting on two walls. Despite the damage, the woman seemed pleased to show me her home.

Khokana is a special place for me, photographically and in a way sentimentally, as illustrated in these images. The photographs fall somewhere between documentary and portraiture. This is unintentional, it just happens. When I visit Khokana it is easy to just let go, let my camera lead me where it wants to go. My sentimental attachment is more difficult to explain. An important element is the people, who are warm and friendly, and accept me as an outsider. Another element is that I feel like Khokana is “my” private finding. I rarely encounter any foreign tourists there, so it is definitely off the beaten path.

In retrospect, I can see parallels between my experience in Khokana and Bhaktapur and my experience nearly 20 years ago during a photography workshop in Havana, Cuba. How so? One of the lessons in the workshop was how to find and meet strangers, get to know them well enough to ask for a photograph, and then return the following day to give them a print. This can lead to a stronger association and to a series of more intimate images. I used this technique when I took my book of photographs with me on my second visit to Khokana. The people there were especially pleased when I gave them the prints. This then led me to return again and again.

In this issue of The Monochrome Chronicles I’ve shown you my series of photographs from the village of Khokana. This is the second in a series of three episodes about Nepal. As I wrote in the introduction, Khokana is a midway point between the city of Bhaktapur (the topic of the previous episode) and the tiny mountain villages that are the subject of the next episode. Khokana plays a special role in my photographic series, being my first introduction to village life in Nepal, and I return each time I venture to Nepal.