This third and final episode based on my work in Nepal goes much farther off the beaten path than either Bhaktapur or Khokana. Imagine if you will a small village, built on the side of a mountain, and consisting of a few hundred centuries-old stone houses. The village is accessible only on foot, an hour and a half climb from the end of the nearest road. The source of water is run-off from higher on the mountain. Traffic consists only of people on foot and the occasional mule train. Far in the distance lies the snow-capped Annapurna range of the Himalayas. Such would be the destination for this series.

In the course of the series, I have visited six villages: Bakhrigau, Bandipur, Bhujung, Dhampus, Galeguan and Ghandruk.

These villages lay in remote areas of the foothills, accessible by 4-wheel drive vehicle or on foot. The stone houses have been passed down from generation to generation within a family for upwards of a hundred years or more. Typically, the homes have no running water and only some have electricity, maybe a single incandescent bulb for illumination of the entire home. My objective in this episode is to show you a few aspects of these villages, specifically home life, work life, and portraits of the residents.

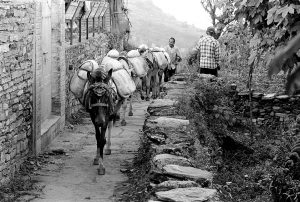

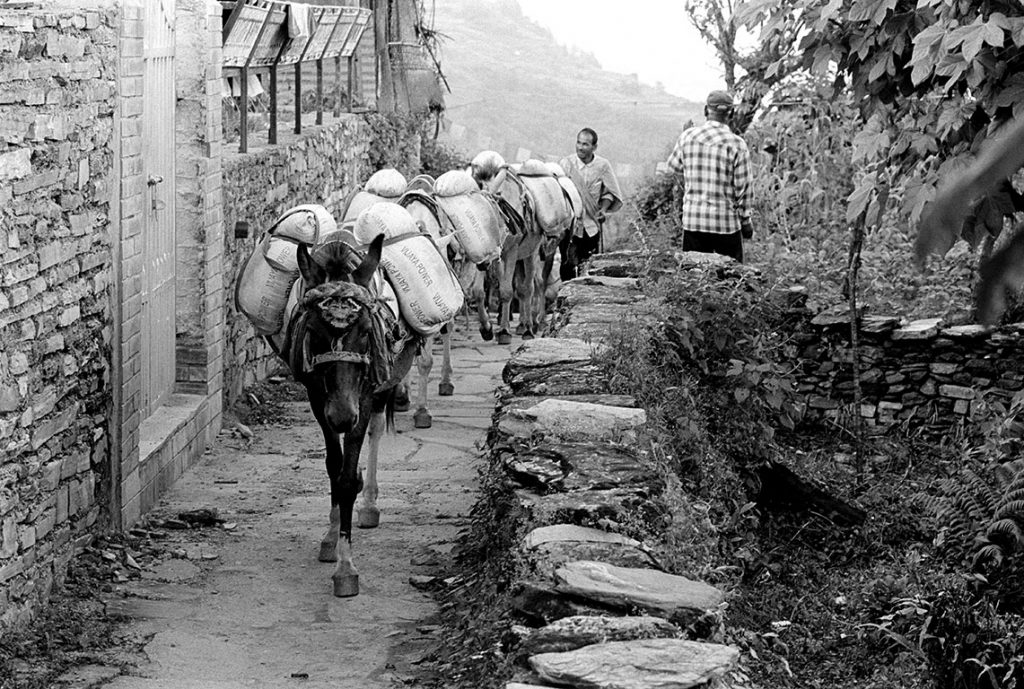

I can scarcely begin to describe the topography of the villages. The stone houses huddle along the curves of the hills with only narrow footpaths and stone steps that connect the houses into one village, an intricate array of man-made structures imposed on the natural contours of the mountainside. Clearly, the layout of houses, stone paths, and other buildings such as a community center, school, Hindu temples and so on, must have evolved over a long period, many generations, probably centuries. The footpaths are too narrow for cars or other vehicles and in the absence of traffic, the villages are pleasantly quiet both day and night.

Before moving to the photographs, let me tell you about my impressions of these villages from my perspective as a photographer and from my personal point of view. For one thing, I am a city person (even though I spent the first 18 years as a farm boy, I’ve lived the last 50 years in Chicago, New York and Tokyo) so these villages came to me as a culture shock. I had not imagined that such villages still existed in the 21st century. Gradually over the last 20 years as I’ve photographed in Southeast Asia and East Asia, I perceive a trend toward more remote, isolated locations. For photography, the villages presented certain challenges. The high altitude (around 2000 meters), fresh air and bright sun combine to create a special, intense natural light. The interior of the houses, in contrast, was dim. Not to mention the challenge of getting to the villages in the first place. My photography has pursued the goal of exploration about the people of these villages and their culture.

In case you haven’t figured it out already, let me say that getting to the mountain villages led me through some spectacular landscape via 4-wheel drive Jeep – and sometimes white-knuckle rides along narrow, rough roads with precipitous fall-off on the edge of the road. Getting to the villages that were accessible only on foot up or down the side of the mountain…need I say more?

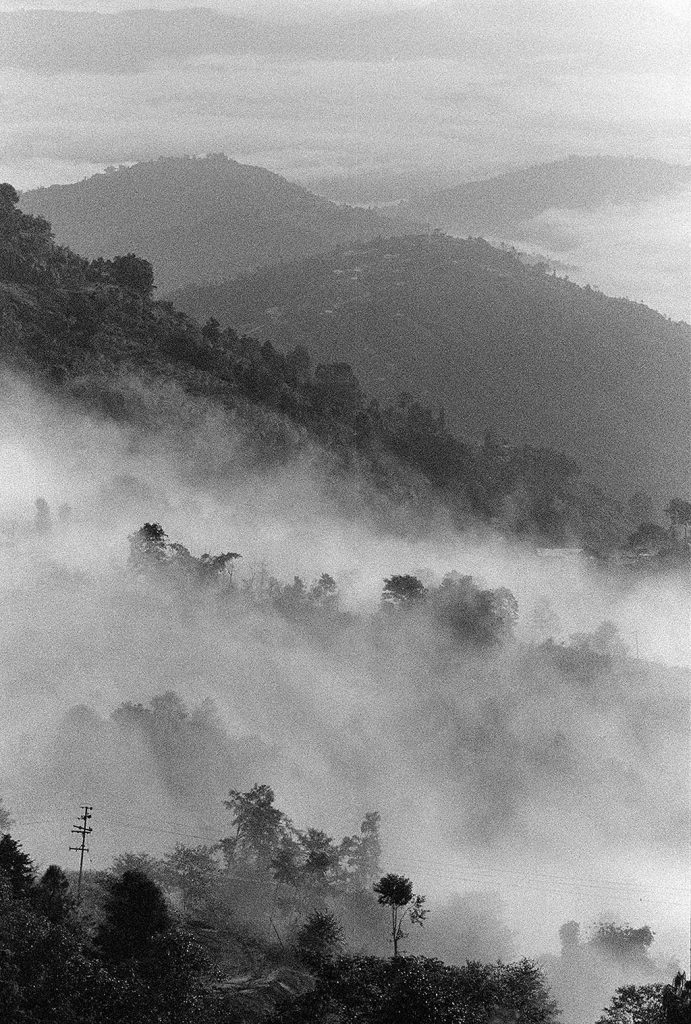

The style of this image reminds me of traditional Japanese scroll paintings, or kakejiku, of mountain views. The scene is looking across a wide valley just after sunrise. The Himalayas lurk in the background. My camera and I sat on the balcony of the hotel room from an hour before until an hour after sunrise. A dense fog, so thick that at times I could hardly see beyond a few meters, crept up from behind and slowly engulfed the valley. The near-total silence and being enshrouded in fog was ethereal. I shot several rolls of film and this one successful frame was the reward for my diligence. For people living in the village, this was a common experience but for me it provoked an other-worldly feeling and transported me to a surreal place.

Village life. I wanted to capture some facets of life in these villages, but how to do this? Street photography, my usual mode, would be moot: there are no streets in these villages. I might describe the extant images as documentary photography but somehow that doesn’t fit. I spent a lot of time on foot, especially early in the morning and late in the afternoon, and gave free rein to my camera and my little inner muse. Collectively the photographs create a portrait of village life.

Some villages have a system of aqueducts that diverts run-off of water from higher on the mountain. A series of shallow waterways runs alongside the stone pathways to provide water to the village. The sound of running water adds to the atmosphere in the village.

Many of the villagers are farmers. Rice is a main crop along with some other grains such as wheat and maize. As for livestock, goats and chickens are raised in the villages and cattle, water buffalo, and yak graze in pastures in the surrounding hills.

In this photograph, the late afternoon sun illuminates the fields and creates the shadows cascading down. The dark trees in the background contrast with the bright field of grass in the foreground, adding to the drama of the scene.

Another crop is honey from wild bees high in the mountains. Hunting for honey is a specialized process with a long tradition. One of the villagers described how they harvest the honey. The bee hives are on the sides of sheer stone cliffs, about 1-200 meters above ground level. Their location is a closely held secret, for the honey is especially rich and flavorful. The men of the village gather the honey collectively by climbing up the face of the cliffs with ropes. Traditionally, they used to climb in the nude, for they feared that if they wore clothing bees might become embedded in the cloth and sting them after they return home. Unfortunately, I have not yet witnessed honey hunting…but this definitely is on the agenda for the future.

Weaving cloth, both for home use and for sale to earn money, is an essential home industry. Some women spin their own yarn from goat hair – the long-haired goats live in a lean-to attached to the house or sometimes in a pen on the front porch. Others make yarn from bamboo.

Weaving the cloth is a team effort. These women were weaving sacks for carrying grain from the fields back to the house, and then to the market.

The composition of this photograph makes it dynamic. The cascade of the four women draws the eye downward and then the fabric on the loom draws the eye back upward again. The result is an understated and yet intimate view of an everyday morning in the village.

Making yarn from bamboo is a distinctive practice. The process takes many days, as described by one of the villagers. First, the bark of the bamboo is stripped off in long thin strips. Then over the course of two days or so, the strips are first soaked in boiling water and then soaked in cold water, again and again and again to separate the bark into course fibers. Next the strips are wound into a loose bundle, which is placed on a stone and then pounded by hand with a club. Each bundle is pounded for several hours, hundreds of strokes with the club, to break the bamboo into finer fibers. Finally, the bamboo is carded by hand to remove unwanted material, then spun – again by hand – to form the yarn. The next step is to weave the yarn by hand to make a sturdy fabric.

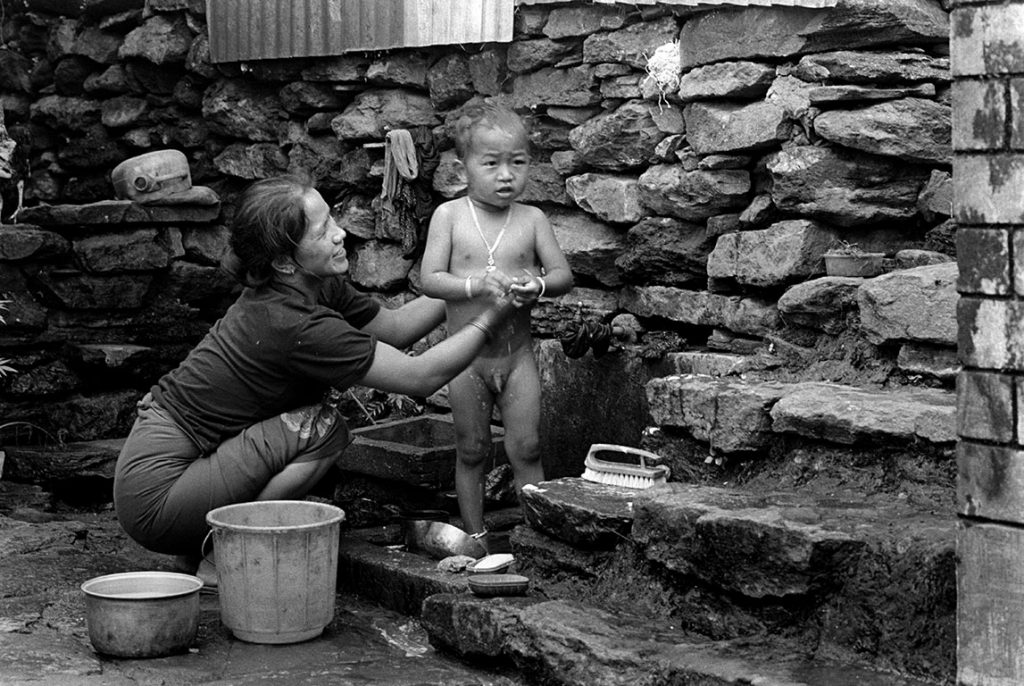

Turning to home life, in retrospect I realize a feature of these villages that, to me at least, is a bit surprising. The front door to the houses is always open during the day. Symbolically this pratice suggests several aspects of daily life there. On a simple level, the interior of the house is dim, since the few windows are small, so leaving the door open lets in additional liglht. On the community level, life in the village is very social so the open door invites visits within the neighborhood. Also the villages are quite safe so the open door is no problem. Finally, many of the activities of daily life – doing laundry, tending goats and chickens, gardening and so on – are outdoor activities near the home, so maybe the open door is just a convenience.

Some of the stone houses are a hundred years old or more, and have been passed from generation to generation within a family. Also, they are multi-generational homes. This woman, who was the daughter-in-law in the household, was cooking breakfast for the family, including the extended family and any neighbors who happened to drop by.

Inside, the houses are dim even during the day because they have only a few small windows. Obviously these are difficult conditions for photography but fortunately she was sitting in the light from one of the windows.

These photographs, then, focus on everyday life in the villages. Of course, sometimes out-of-the-ordinary events occur, too. One of the villagers told the story of the time he found that a leopard was poaching his chickens. He and his neighbors, armed only with clubs and stones, set out to capture the leopard (local law prohibits killing them). They found and chased the animal who ran back to the village and into one of the houses. The villagers quickly closed the door, trapping the leopard inside. What to do then? One of the villagers climbed up to the roof and dropped down into the house, and at the same time one of the villagers opened the door. The man inside the house then chased the animal, which then ran outside where the rest of the villagers attacked him with clubs and stones. The villagers considered this killing to be justified as the leopard was a menace to the village, but still they buried the corpse in a hidden place lest the local authorities learn about it and punish the village.

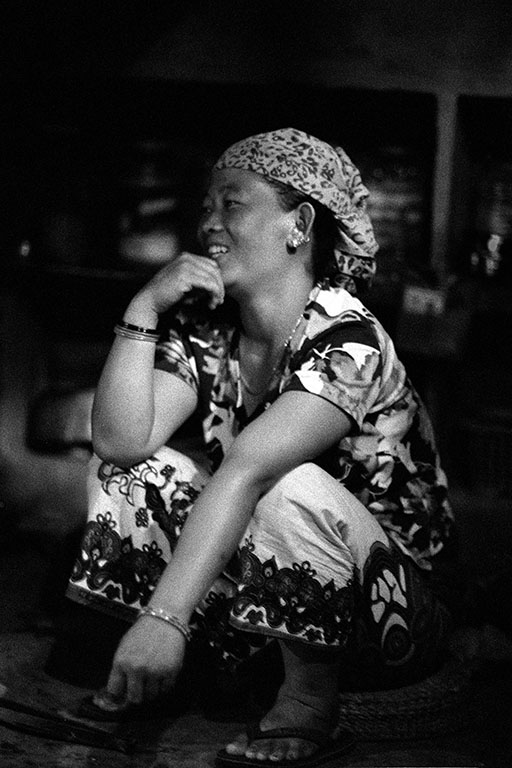

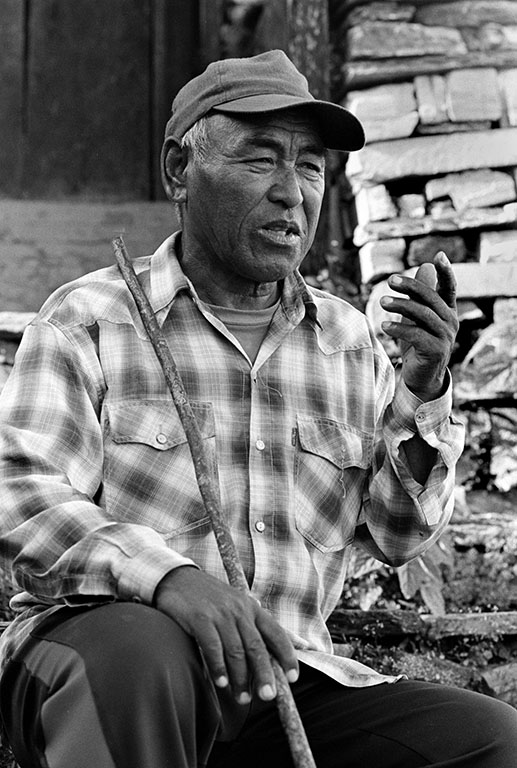

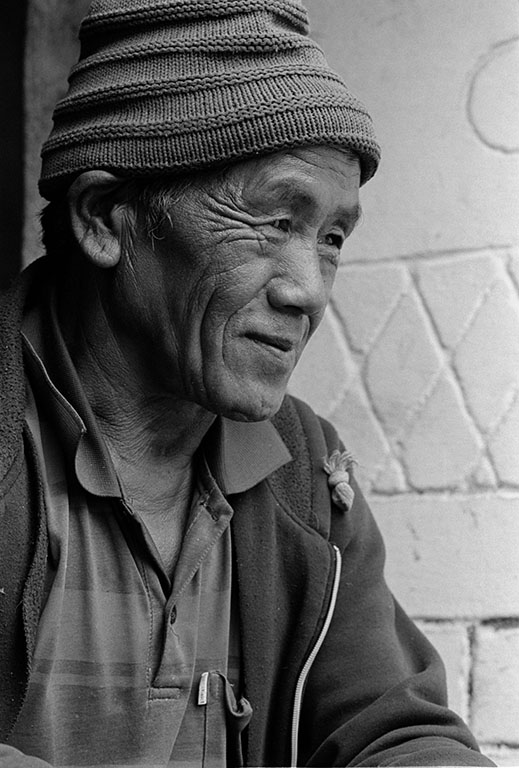

Portraits. What more can I say over and beyond what I’ve already said about portraiture from Bhaktapur and Khokana? Portraiture is a technique but a successful portrait must go beyond mere technique. It must go deeper than just how the person appears on the outside. It requires trust and both verbal and non-verbal communication. I can rely on a guide for verbal communication with a subject when I don’t speak the language; but then I must rely more on non-verbal communication, with the caveat that non-verbal expressions are culturally driven.

Pardon this perhaps unnecessary rationalization about portraiture. The reality is different for me. Once I am in the field, so to speak, I have to dissociate myself from my rational side. My camera leads and I follow. I heed my little inner voice. Somehow this is easier for me in the mountain villages, where everything is outside my usual boundries. I approach my goal of “no limits” photography. I have to pursue these images. I have no choice.

For the portraits in the mountain villages, I modified my usual technique. Typically, I tend to favor close-up images. I’m not sure just why this is, but maybe it has to do with the feeling of intimacy, of breaking down the barriers between me and my subjects. Does that sound odd when most of my subjects are passing strangers? So be it. For the mountain villages series, and to some extent the work that preceded the series, I decided to step back more to take in some of the subject’s environment, to add another dimension to the portraits.

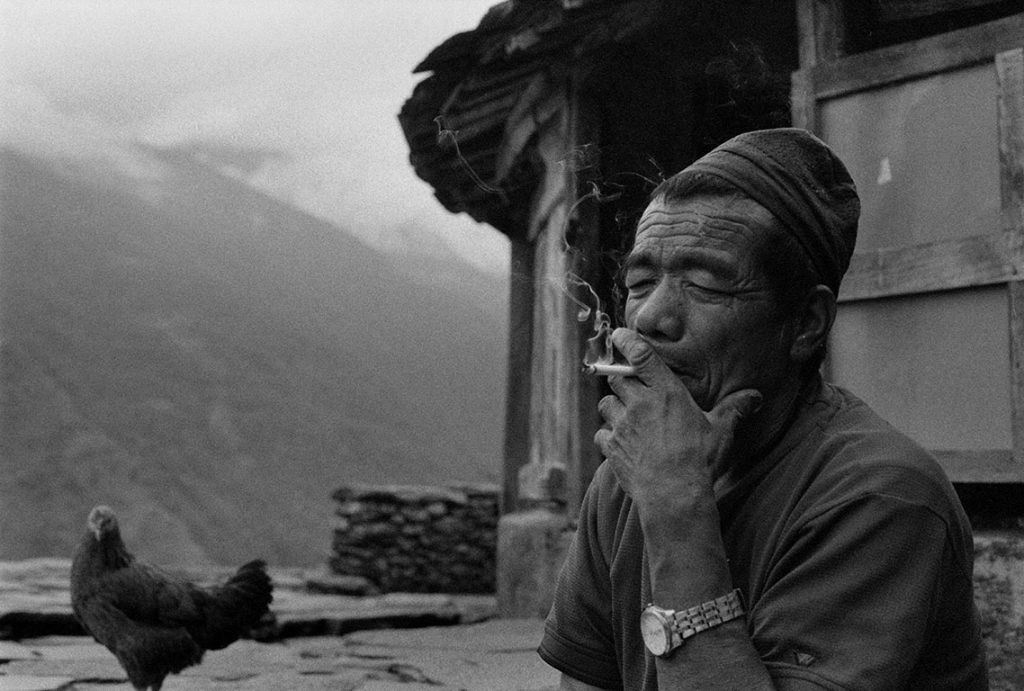

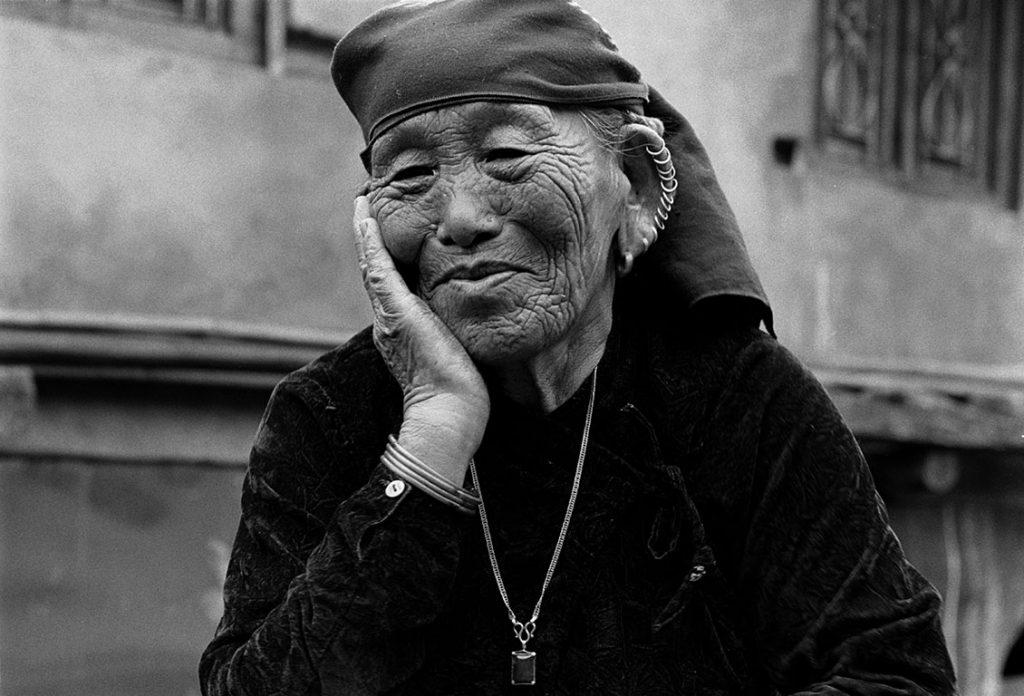

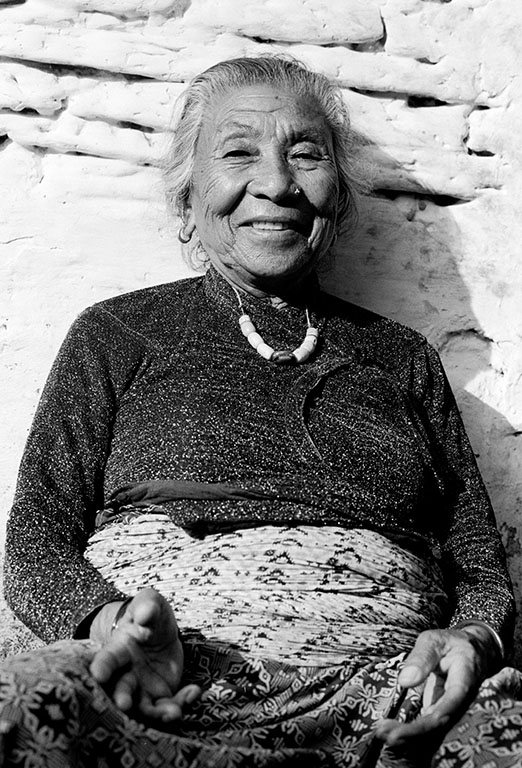

Not surprisingly, older people have been a focus for my photography in the mountain villages, a trend that started with my photography in the Nam Ou Valley of Laos. Longevity is common among the villagers in Nepal. Probably the simple diet, fresh air and hard work contribute to their long lives.

The subjects in these portraits, as indeed most of the people I’ve photographed in Nepal, were quite amenable to me and my camera. This rather surprises me as I was clearly a foreigner (and I rarely if ever encountered another foreigner in the villages). Dare I suggest that this was in part because I learned to ask permission using the Nepali language? The experience goes much deeper than that, I think. Nepali people generally are quite social and accepting of outsiders, in my experience. This is part of the spirit of the Nepali culture. They made me feel at ease.

The key elements of this portrait undoubtedly are her face and the supporting gesture of her hand. What stories, what memories those wrinkles must hold. Though the sides of her mouth turn slightly down, still there is the hint of a smile, as there is also in her eyes.

I am convinced that the light in these locations confers a distinctive aura to my photographs. Due in part to the high altitude and thinner air, the sunlight seems to be more intense, and I learned to adapt my technique both in the field and in the darkroom. The result, I feel, is a greater depth and richness in the images compared to some of my other work.

So, some of my impressions from my visits to mountain villages in Nepal. I can scarcely put into words my experiences there, and my photographs cover only a small fragment of the lives of the villagers. The morning of my last day in Galeguan, again just before sunrise, my guide Amit took me to visit a Buddhist temple situated near the place where the water from seven wells converges into a small pool. Local legend holds that if someone makes a wish at the well that wish will come true. My wish? That I have enough time to complete all my photography.

Let me finish with this haunting, evocative image. First I’ll discuss the image per se, and then maybe I’ll give you the background.

The other element of the photograph, of course, is the two hikers walking down the road. In striking contrast to the rest of the photograph they are distinct and in focus. Is it my imagination, or is it clear that they are villagers? Lastly, and at the risk of over-analysis, this one image symbolizes for me the path I travel during this series. Sometimes I feel that I have no clear roadmap to guide me. The path ahead may seem indistinct. And that doesn’t matter. I go forward trusting that my camera and my little voice will guide me.

The reality is more pedestrian and maybe I should omit this description. Along the way down the mountainside, we stopped to chat with this couple who were walking to the market to sell the baskets that they had made by hand and were carrying on their backs. They told us it would take a full day of walking to get to the trading center down in the valley. And another day’s walk to return home. Such is daily life in these villages.

This episode of The Monochrome Chronicles is the third and final one about my photographic series from Nepal. Without doubt, my experiences there have influenced me greatly, both photographically and personally. On my first visit to Nepal, I had no clear expectation about what I would find there. It was just another destination that I would add to my list of “countries visited.” By the end of a week I knew I would return, as I have done four times so far. Each time I returned to Bhaktapur and Khokana, I discovered deeper and deeper levels of their culture. My experience in the mountain villages differed in that each year I visited different villages, thereby finding a wider range of local cultures.

As the series unfolded, I felt a gradual widening of my point of view. At first, not surprisingly, I was awed and maybe a bit overwhelmed because everything was just so new to me. Gradually I realized that I simply had to let go, put aside any pre-conceived ideas. I stopped seeing things as “different.” The Nepali culture simply is. The one-hundred-plus ethnic subgroups just exist. Each day begins anew. Around every corner, beyond each bend in the road…well, who knows? OK, this may sound a tad Pollyanna-ish but when people ask why I return to Nepal so many times, that is the answer.

Ultimately, though, the biggest influence has been the spirit of the Nepali people. This spirit is what unifies the three segments of my series – Bhaktapur, Khokana and the mountain villages. Nepal is calling me back.