Now I turn to a series that is close to my chest. Sanja Matsuri, a street festival in Tokyo that takes place every year on the third weekend of May in the neighborhood of Asakusa, has drawn me back nearly every year since 2004. What keeps me coming back?

Sanja Matsuri evokes myriad memories for me. A huge throng, some 1-2 million people, who crowd the streets over the weekend. As many as 100 portable shrines known as mikoshi from 44 temples in the surrounding neighborhoods threading through the crowds, borne on the shoulders of members of the temples. Revelers wearing light cotton jackets, the colors and designs identifying their home shrine. Musicians with Japanese taiko drums, cymbals and flutes interspersed with the mikoshi. Mikoshi bearers chanting in unison, “wa-shoi, wa-shoi,” blowing police whistles and shaking the mikoshi so that their bells chime out. As Sanja Matsuri is one of the three largest festivals in the city, Asakusa is extremely crowded during that weekend.

Sanja Matsuri, one of the oldest matsuri in Japan, dates back at least three centuries to the Edo period (1603-1868). The festival lasts three days, from Friday afternoon to Sunday evening. The main event is the parade of mikoshi on Sunday, beginning early in the morning and continuing until after sundown. Some 100 mikoshi form the parade, which begins at Asakusa Shrine and then divides into three parades to follow different routes through the neighborhood. The three parades eventually converge again in the evening.

The main mikoshi are huge, weighing about one ton, and 40 mikoshi bearers are required to carry each one. Mikoshi from the local shrines are smaller but still require teams of bearers to carry them. The smallest mikoshi are carried by children.

A key feature of the mikoshi is that they are carried on the shoulders of mikoshi bearers. In this series, I have focused mainly on the mikoshi bearers, but first a few words about the mikoshi per se. They are made of dark lacquered wood and decorated with gold emblems and gilt. On the top stands a golden bird, called a “hou,” a kind of Japanese phoenix. For the matsuri, the mikoshi also bear colorful silk ropes and garlands of zig-zag shaped white paper streamers. The shrine itself sits atop a matrix of wooden beams, lashed together with rope.

Mikoshi bearers

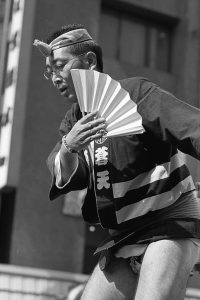

The mikoshi bearers are volunteers from local shrines. Carrying the shrine is hard work, especially when the sun is hot. In addition to carrying the mikoshi, they chant in unison and march in unison. Occasionally, they shake the mikoshi either left and right, or up and down, to make the bells ring out. Although the parade lasts all day, the members rotate among themselves so they can rest.

Some one hundred mikoshi are in the parade and dozens of bearers carry each one. Despite this, at times I can catch eye contact with individual members.

During the first few years of going to Sanja Matsuri, I mostly stayed on the sidelines among the spectators. This was partly because of what I perceived as respect for the parade and partly because the parade organizers and the police encouraged spectators to stay off the streets during the parade. A reasonable precaution. Then one year a Japanese photographer grabbed hold of my arm and said, “Come this way.” When we got onto the street and close to the parade he said, “Now take pictures. It is safe.” Since that time I’ve always gotten close and mingled with the parade participants, sometimes perilously close. That Japanese photographer was right, getting close to the action is the key to good photography. I don’t know who he was, had never seen him before and he disappeared almost immediately after he released my arm.

The parade lasts all day and into the early hours of the evening. This image, taken close to sunset, reveals the intimacy shared among the mikoshi bearers even so late in the day.

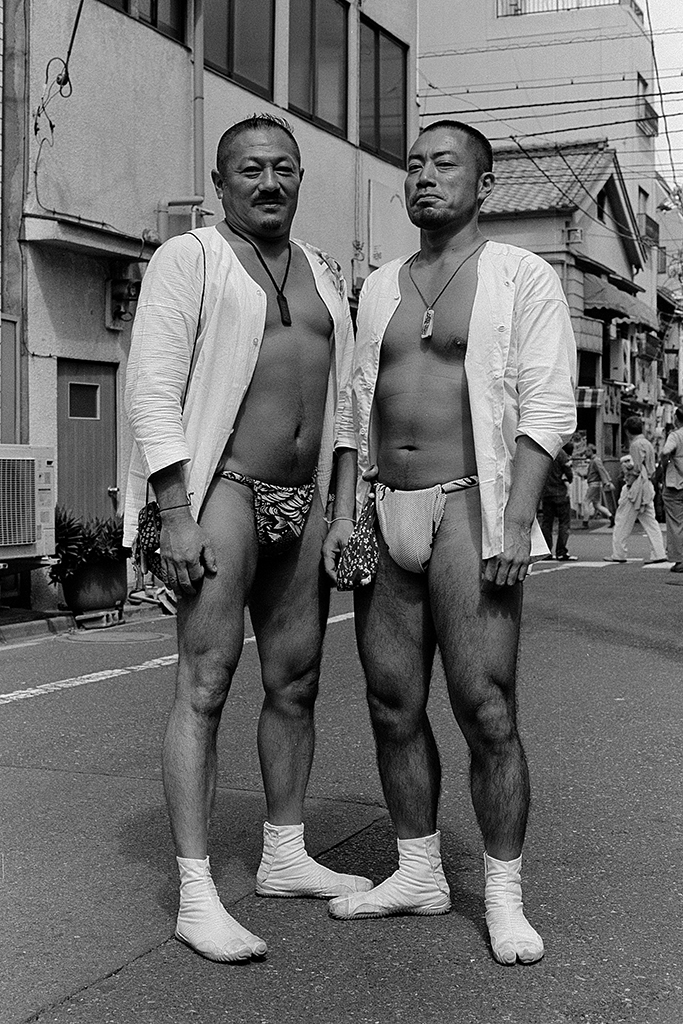

Mikoshi bearers assemble very early in the morning on Sunday, maybe 5 or 6 o’clock, to get into position for the parade. Then they spend several hours carrying the heavy mikoshi and usually the weather is very hot. By late afternoon they are so tired. Underneath their happi coats they wear light-weight cotton undershirts and some wear fundoshi (Japanese-style loin cloth). When they are not actually carrying a mikoshi they often wear just their undergarments as in this image.

Shrine attendants in white robes and black caps participate in the parade as well. Some carry taiko-like drums. Others carry wooden donation boxes (saisen) suspended on poles over their shoulders. I’m tempted to comment that these shrine attendants add a lot of color to the parade although the predominant color is white. With their long white robes flowing in the breeze, they do contribute to the overall texture of the festivities. In contrast to the rest of the participants their demeanor is quite solemn.

Spectators

Sometimes as a photographer I focus not on the event itself but on the people surrounding the event. This certainly is the case for Sanja Matsuri. Some people avoid Sanja Matsuri because the crush of spectators is overwhelming. I look forward to mingling with the crowds. I can become anonymous, or even invisible. Then, people become the focus of my photographs. Out of the million or more people who attend Sanja Matsuri each year, I manage to focus on individuals.

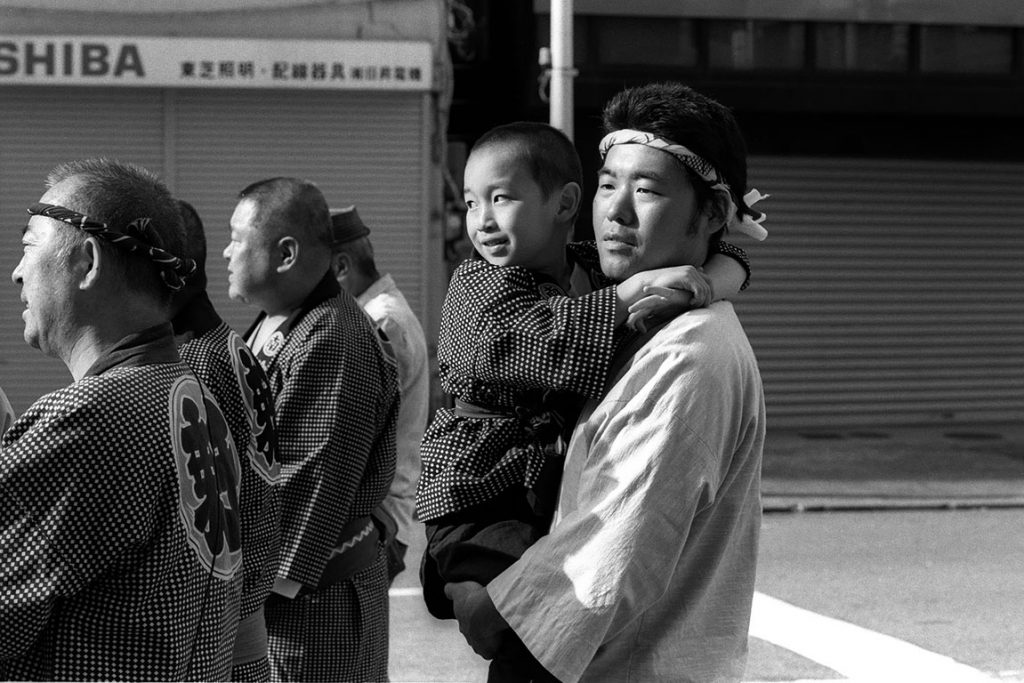

As the French photographer Cartier-Bresson said, sometimes the key is to get into position and then wait until the right moment comes along. This was a moment during Sanja Matsuri but also detached from the festivities, late Sunday afternoon when the sunlight is so rich. Theoretically, the composition is unbalanced but that doesn’t matter. Or maybe that is the strength of the image. The intimacy between the man and boy (presumably father and son) is what enlivens the image. Another moment in time frozen on film.

Occasionally, I just stand and watch the parade of people pass by rather than watching the parade of mikoshi. This woman seemed to be so calm, so dignified. She stood out among the rowdiness of the matsuri.

This man was looking right into my camera, but what was behind that facial expression? I was standing still, as usual, and he was walking past with the parade, so I didn’t have a chance to find out more.

My approach to photographing people varies. Sometimes I keep my distance, watching from the sidelines as it were. This often works well for street photography when the goal is to capture people being themselves. It obviates the issue that the presence of a photographer influences people’s behavior. Other times I am, for some reason or another, drawn to a certain person. Then I approach that person directly. Sometimes I strike up a conversation. Other times I simply ask permission to take photographs. In this instance, I took the direct approach. He readily consented. Why did I single him out? Maybe it was his lush full beard, which is unusual for Japanese men. I try not to analyze this. One of the keys to photography, especially street photography, is to listen to that internal little voice.

OK, here is a side story. This day I was taking a break from the main parade route and wandering around a local neighborhood. I noticed one group gathered on the sidewalk in front of a bar. All of them men, mostly in their 30’s and 40’s. After a while I noticed these two guys standing in the street and talking to each other. At that point their white cotton jackets were buttoned up. I asked permission to take their photo, which the guy on the left readily granted though the other was a bit reluctant. Then I asked them to show me their fundoshi. With only a little persuasion they agreed. Both of them were looking directly into the camera, but wore such different expressions on their faces.

On Sunday evening, the third and final day of the matsuri, all the 100 or so mikoshi converge on the main temple of Sensoji in the early evening for a final procession to pay respects to the gods. While waiting for the procession, these two guys were talking animatedly together. Clearly, they were friends but I photographed them separately. Sunday evening is a more subdued part of the festival.

Three more guys waiting for the final procession of mikoshi. Japanese people generally maintain a distance when speaking to each other, even among close friends, but not these three. Two things strike me about this photograph. The first is the quality of the light, which captures the intimate mood. The second is the facial expressions of each man. Especially the guy in the middle looks plaintive. Sometimes I think the composition is off, the third guy is half-way out of the frame, but overall I think it works. It adds another dimension to the image.

This woman, though she was with a group of people, seemed to be isolated from them. What was behind that wistful look on her face? By the way, men wear headbands made of tightly wound cloth. Women, on the other hand, wear this style of headband.

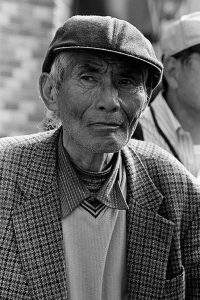

Most spectators at Sanja Matsuri focus on watching the parade of mikoshi, and the rest of the events. In this image my point of view was in the reverse. This older man was standing among the spectators, but his eyes seemed to be far, far away.

Sanja Matsuri is a noisy boisterous event, especially during the parade, which must disrupt the lives of people who live along the parade route in the smaller residential neighborhoods. Many residents of these streets join the festivities, having parties on the sidewalks and so on. These two people had a bird’s eye view of the matsuri from their second floor windows. In the absence of the context about the parade, though, both images would project a somber, wistful mood.

What was going on here? These guys were hanging out on the corner of a back street of Taito ku. I don’t know what attracted my attention, but I stood across the street for a while just observing them. At first two of them were watching some young boys playing in the street. Then three more guys joined them. The men were wearing white cotton jackets, long pants, and white tabi sandals, which many wear during the matsuri. At one point two of them lifted their shirts to bare their stomachs – a curious moment among friends.

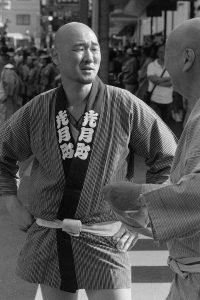

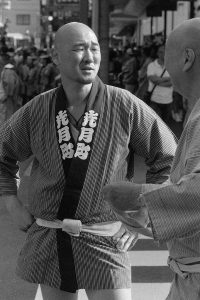

Saturday is largely a social time during Sanja Matsuri, I think. Most of the streets around Sensoji temple are closed to traffic, many izakaya set up tables on the sidewalk to cater to spectators, and mobile food venders abound, too. People wander along the streets and stop to chat with each other, like these two men were doing. This image also shows well the happi coat that mikoshi bearers wear. The name of their shrine is printed on the lapels.

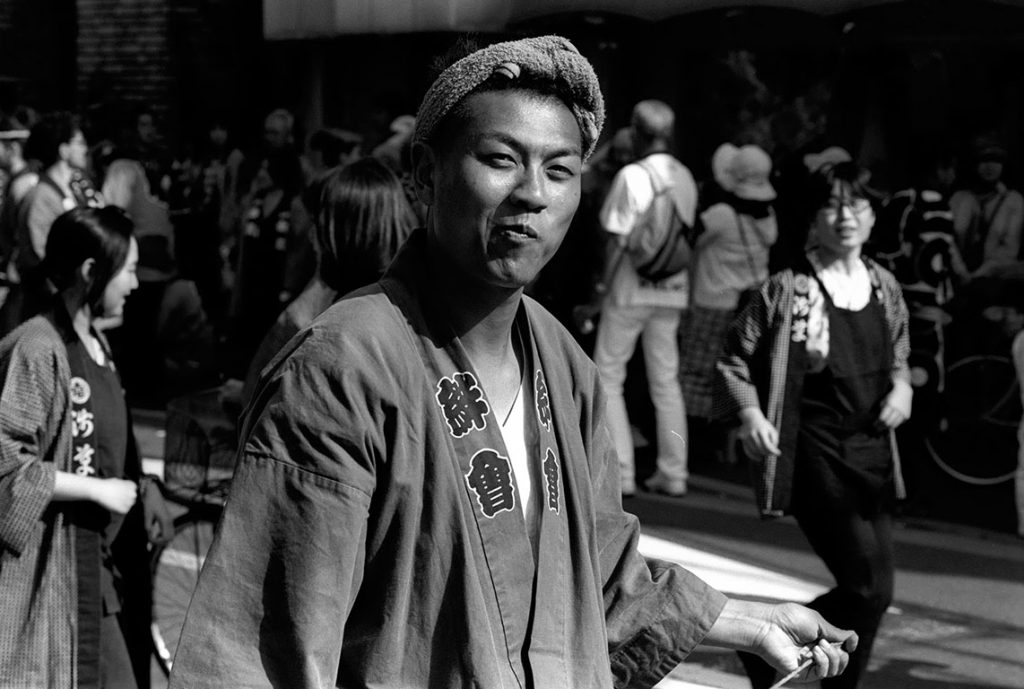

Late Sunday afternoon and the matsuri was winding down. A couple of blocks away a large group of mikoshi bearers wearing the same distinctive happi coat as this guy was congregating. This man came walking alone down the middle of the street, headed directly toward me. Heeding my little voice, I began photographing him as he approached. Eventually, he broke out into such a big grin. Just a brief moment of silent communication.

The parade route travels through the neighborhoods surrounding Sensoji Shrine and wends its way along many side streets, which tend to be lined with neighborhood pubs, or izakaya. These four, maybe the izakaya owner and his friends or family, were sitting outside the pub enjoying beer and lunch while watching the parade.

In the midst of the raucous noise and near-pandemonium that envelopes most of the neighborhoods surrounding Asakasa, these three people managed to find a quiet spot for a tete-a-tete.

Another street corner in Asakusa 3-Chome after the parade had finished. In this case, I cannot venture a guess what these two guys were up to. Both were wearing the white uniform that mikoshi bearers wear under their happi coats.

This sentimental image, not characteristic of my photography because I usually avoid photographing children, captures a moment at the end of the parade on Sunday.

So, this episode of The Monochrome Chronicles has focused on Sanja Matsuri. Little did I realize at the time of my first visit in 2004 where this series would take me. Or even that the experience would turn into such an extended series. What draws me back year after year? The answer to that question has evolved over the years. At first the matsuri itself, which is deeply rooted in the culture of Japan, drew me back. Next the symbolic and religious elements of the mikoshi and the parade drew me back. Over time, however, it has been the people who have drawn me back. So many people, such a wide variety of people, and yet I could see some of them as individuals. The series will continue.