This is the second installment of the Monochrome Chronicles recounting my project to visit all 47 of Japan’s prefectures. The topic this time is izakaya. Before moving on to the photographs, a discussion of the izakaya is in order since it is unique to Japanese culture and some readers may not be familiar with the practice.

Soliloquy about izakaya. Izakaya have become my favorite kind of Japanese restaurant, though “restaurant” is a misnomer for the izakaya, which are more akin to a pub or tavern. Throughout my travels in the 47 prefectures, I usually seek out an izakaya for my evening meal. I do so for several reasons. Izakaya, and especially the taishu izakaya (blue-collar izakaya), reflect the local culture. Sometimes, rarely but sometimes, an izakaya is a chance to meet and talk with local Japanese people. In izakaya, conversation is the norm. At times the Japanese, despite their reputation for being shy around strangers, make the first move to begin a conversation.

Also, a meal at an izakaya is an introduction to local food. The menu, or at least the specials, vary daily. Speaking of the menu, in Tokyo the menu usually has photographs of the choices, and sometimes even an English translation. Not so in the more remote cities and towns, where the menu is only in Japanese. Sometimes it is written on a blackboard or on strips of paper thumbtacked to the wall, or handwritten on a sheet of paper. Then, being practically illiterate in Japanese, I have to negotiate with the waiter or maybe even directly with the cook.

My ultimate reason for preferring an izakaya is the food, which usually is more delicious than in restaurants the cities. The fish is fresh from the sea. Salad items, vegetables and fruit come from a nearby farm or somebody’s garden. Everything is prepared by hand and cooked to order.

And, of course, I practiced my not-street photography in my search for izakaya.

“Not-taken” Photographs

Like most photographers, I have a storehouse of mental images for which I wish I had taken photographs but didn’t for some reason. I call these images “not-taken” photographs. To add more flavor to this episode of TMC, I’ll describe some of them at intervals in the text.

“Not-taken” photograph: “This evening in a small basement izakaya in Aomori, named Rokube, I remembered why I’m making this 47-prefecture journey. Down one flight of stairs from sidewalk level, low ceilings, dim lights, two narrow rooms – one with counter seating for eight people, the other a tatami room – and with nostalgic music from, I would guess, the 1950’s. A Mom-and-Pop izakaya, the food delicious. As I paid my bill, only 2200 yen, the song, ‘Itsy bitsy teenie weenie yellow polka-dot bikini’ was playing – sung in Japanese.” From my travel log for Aomori, 2018

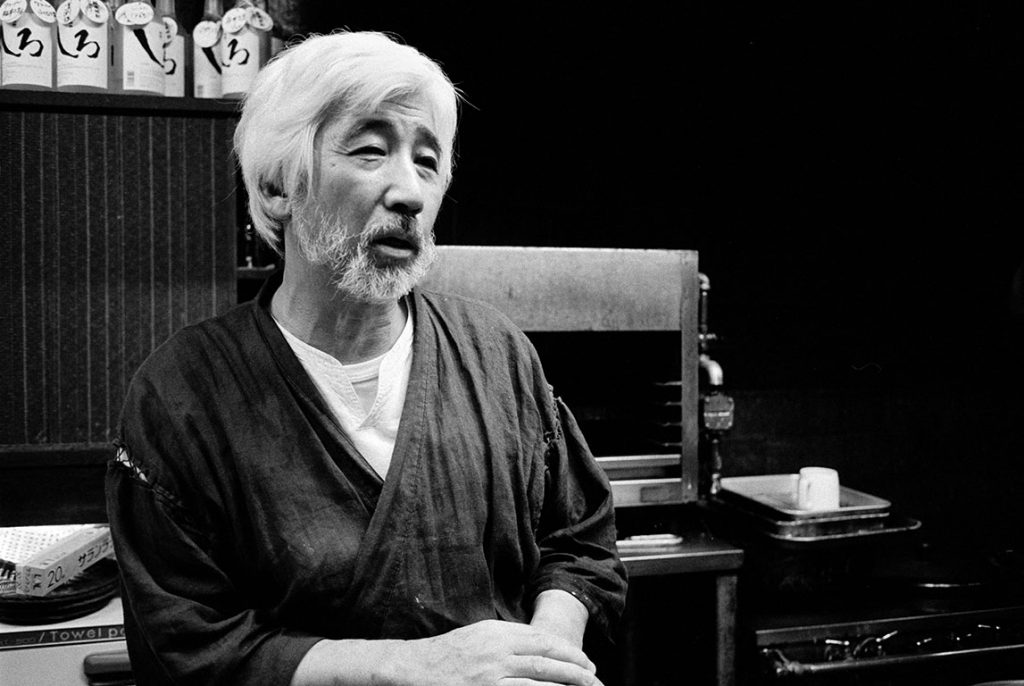

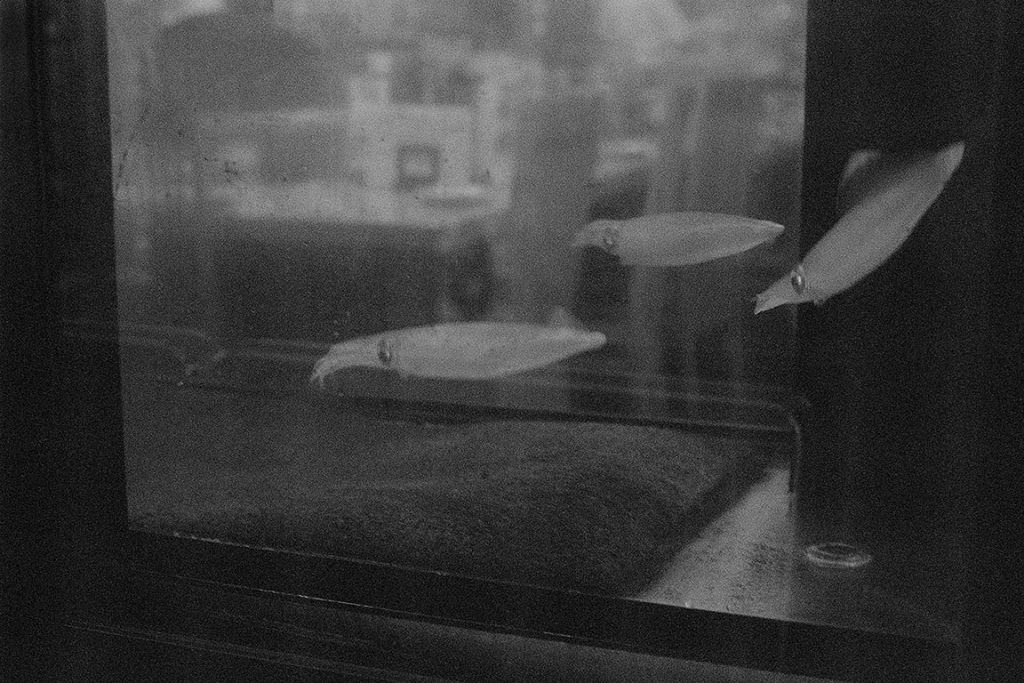

This encounter took place some 16 years ago but how well I remember. You may question whether I remember the encounter or I remember the photograph. Maybe it is a little of both. Would it help to convince you if I told you that during the meal I ate anago (conger eel) for the first time? And that I saw the eel swimming in a tank behind the bar before dinner? A Japanese colleague from NYC took me to this, his favorite, izakaya somewhere between Kyoto and Osaka, where he chatted with the owner and his wife as old friends do.

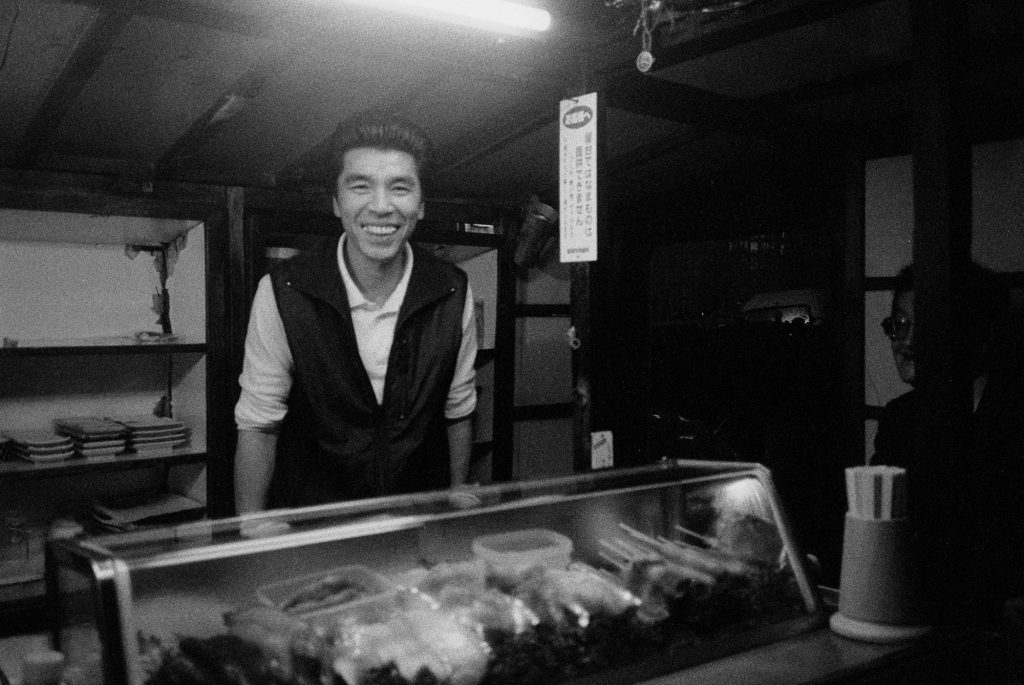

These izakaya usually are compact and intimate, which facilitates communication between the customers and owners and staff. At the best of times, when they discover I can speak Japanese, they include me in the conversation. Then I feel comfortable enough to ask permission to take their photographs and they generally agree.

Yankii Nihongo

A side benefit of my journey through the prefectures was the chance to practice speaking Japanese, or yankii nihongo. Literally, this slang phrase means a foreigner (Yankee) who speaks Japanese (nihongo). I take it as a term of friendliness. I will include some of my (mis)adventures in yankii nihongo in this episode.

Yankii nihongo: My travels around the prefectures have broadened my experience of local Japanese foods and also my repertoire of kanji (Chinese) characters in Japanese writing. For example in one izakaya, the phrase 毛むくじゃらの猫の舌の米飯 in the section for rice and noodles completely baffled me. The only character I recognized was 米 for rice. The waitress kindly brought me an English menu where the expression was translated as “hairy cat’s tongue rice.” This piqued my curiosity and I ordered it. A mound of warm brown rice in a small bowl was topped with dried fish flakes – which did look rather like the hairy surface of a cat’s tongue. It was indeed rice but without the cat.

Izakaya Food

Some food that may seem strange to Westerner’s taste is available in the izakaya. Chicken gizzard sashimi, horsemeat sushi, fat from the neck of a horse (“tategami” in Japanese, which literally means “makes the hair stand up” but in this case it is the horse’s mane that stands up), shish kebab of pig rectums, the list goes on and on.

One of my most unusual experiences with food took place in Tokyo in a stand-up izakaya, where the tables were chest-high and people ate standing up. The tables in this izakaya were long and narrow so typically two or three groups could share one table. During the meal, the waitress brought a plate of food and served it to the group standing next to me and my friend. Soon the aroma wafted past me and, yikes, it was the most revolting stench I’ve ever experienced, like overly ripe cow manure from a barn that hadn’t been cleaned for far too long. I almost retched. Then the man standing next to me, a stranger, turned to me and said with a grin, “This is kusaya. It is delicious. Won’t you try it?” In truth, it was delicious. Kusaya (literally, “stinky fish”) is fermented, marinated fish…supposedly marinated at room temperature on the back porch for several days. Sounds terrible, smells worse, but it is quite tasty.

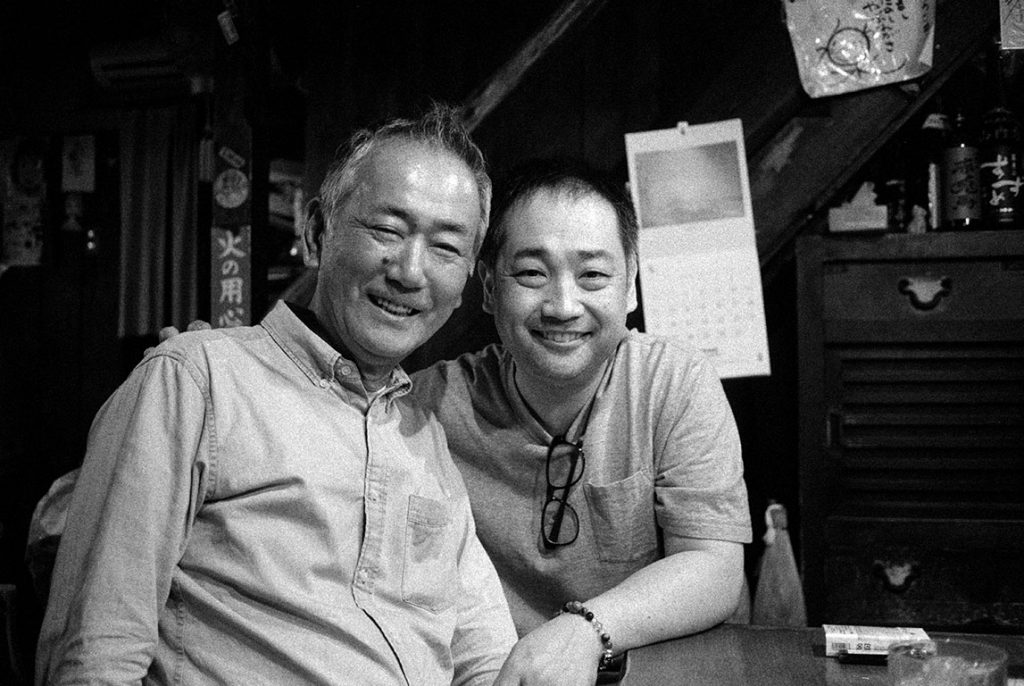

A fugu (or pufferfish) restaurant sat on a back street a few blocks from my hotel. It was small, with only a few tables and five seats at the counter. Almost before I sat down at the counter, the man two seats to my left proclaimed his astonishment at my ability to speak Japanese. Not to be outdone I replied in Japanese, “Are you surprised?” and he replied, “Sure.” Thus began an extended conversation with these two guys. Garrulous describes him, or drunk if you will. Later he showed me the day’s drink menu for Nihon shochu, which listed maybe ten varieties, and boasted that they had tried them all that night. As they were leaving, we shook hands many times and they gave me a hug in farewell.

This image basically is a snapshot. I rarely take snapshots but sometimes the situation is right. Japanese people frequently take snapshots of one another in restaurants. In this instance, one of the guys initiated the exchange of snapshots by taking a picture of me and the other guy. Then I was more comfortable taking a couple snapshots of them.

Taking photographs under the conditions in an izakaya is a challenge. First, am I a participant or an observer? As a photographer I want to step out of the scene and be an observer. On the other hand, the atmosphere in an izakaya and especially the people draw me in, make me a participant. Secondly, the interiors typically are intimate, with lots of old wood paneling, low ceilings and dim lighting. Not conducive to photography.

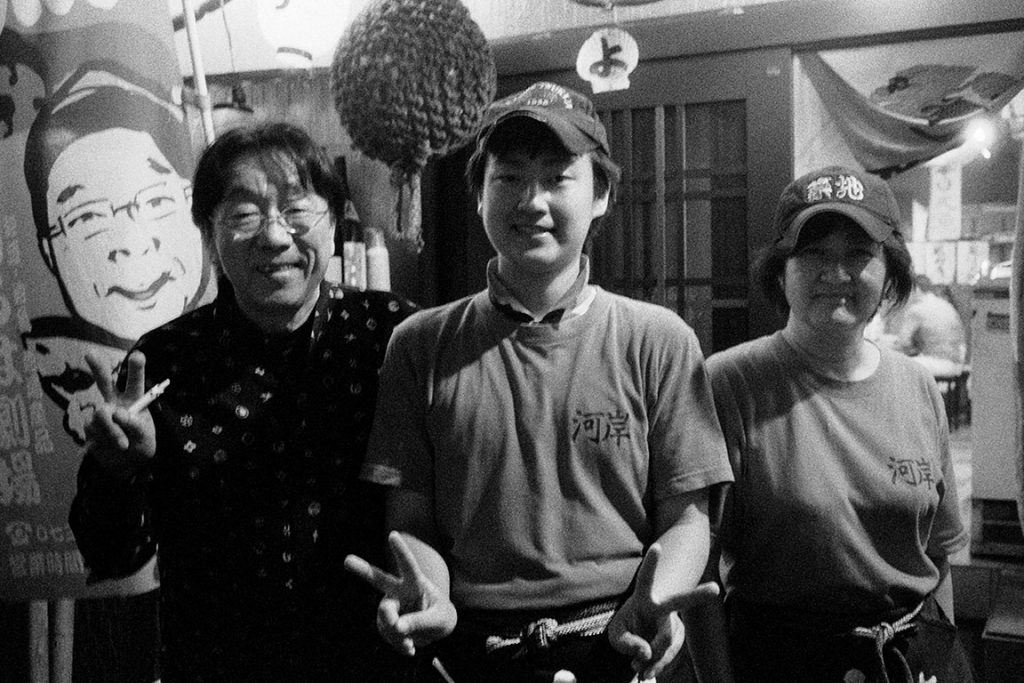

Downtown Tokushima on the island of Shikoku was quiet, the sidewalks were mostly vacant, and few restaurants or shops were open. Tori Tori Izakaya was touted as serving awa-odori chicken, which confused me because awa odori is a style of street dancing popular in Shikoku. Later I learned that awa odori has a second meaning and is a strain of chicken from Tokushima. The yakitoriya was small, dimly lit and crowded but there was one vacant seat at the counter. After I negotiated my order with the waitress, I struck up a conversation with the young man in the next chair. He was very loquacious and we had a lively conversation throughout my meal.

A not-taken photograph. “Again, this evening reinforced my reason for this 47-prefecture project when, rejecting the suggestions from the tourist information center and the hotel clerk, I opted for a small local yakitoriya called ‘Maguro’.…The staff at the izakaya greeted me with ‘You speak Japanese, OK?’ I didn’t know whether to reply ‘Yes, I speak Japanese’ (in English) or ‘Hai hanasemasu’ (in Japanese). I settled on a compromise, ‘Hai, OK desu.’” from my travel log for Akita, 2018

The interior of Maguro Izakaya was like the interior of a rough barn with dark wood. It was both spacious and intimate. Spacious because the interior was one big open room and intimate because the room was divided into three sections, each with lots of dark wood and dim lights. At the front was a room-size open space with concrete floor and dark wood on the walls and beamed ceiling. In the center was the kitchen, surrounded on three sides by counter seating. And in the back was another section with a few low tables where customers sat on the floor. I sat on a stool at the counter and soon met the two people sitting on my left, and the man on my right. They were very chatty. One of them had recently moved to Akita from a smaller town in Tohoku and extolled the advantages of Akita. They tried to persuade me to move there.

Waraku Izakaya in Kagoshima, 2015. “Then the evening was topped off by dinner at a local izakaya, Waraku, recommended by the hotel desk clerk. Small – 5 seats at the counter and a couple of tables in the rear – Mom-and-Pop place. I ate alone at first, but the oba-san kept the conversation flowing. They were surprised that I could speak Japanese, I guess. Later, three other diners arrived one-by-one, but obviously they were regulars. More ‘Oh, you are so Japanese,’ from them. When I made to leave and asked for a restaurant card, one of the regulars quipped, ‘You are real Japanese, ne.’ All three stood up to bid me good-bye and we exchanged business cards.” From my travel log, for Kagoshima, 2015

The style of this photograph is almost abstract, I think. Obviously, it is a close-up shot of the tank. In the background is the interior of the izakaya, visible through the front window and distorted by the glass of the tank.

Yankii nihongo. Usually I prefer to eat at a local taishu izakaya or else at another type of casual diner known as an “akachochin izakaya” (which has a red lantern, or akachochin, hanging beside the front door). One evening in Tottori, I asked the desk clerk at the ryokan to recommend a nearby izakaya. “What kind of izakaya do you like?” he asked. I meant to say, “Akachochin izakaya,” but instead I said “Akachan izakaya.” My reply confused the desk clerk because “akachan” means baby. He could not understand what I meant by an izakaya for babies. I realized my mistake and said, “Sorry, I meant akachochin izakaya.”

Japan offers other eateries that are even more casual than the izakaya. Okonomiyaki-ya, monjayaki-ya, ramen-ya, soba-ya. All these terms end with the suffix “-ya” which simply means a shop. Okonomiyaki and monjayaki are similar, at least in my mind, because both are a one-dish meal like a crepe that is cooked on a griddle. In an okonomiyaki shop the cook makes all the food on one large gridle whereas in a monjayaki shop each table has a small gridle, the waiter brings the ingredients and diners make their own food. In contrast, the main fare for ramen and soba shops is noodles, white noodles for ramen and buckwheat noodles for soba. Ramen is served in a hot soup, which varies depending on the region. Soba is served either hot or cold, and either with soup or a dipping sauce.

Okonomiyaki, Japan’s version of McDonald’s hamburgers, is almost synonymous with Hiroshima. It is difficult to describe. Part omelet, part taco, part crepe stuffed with cabbage. And cooked on an open griddle. I went to a small diner in Hiroshima that served only okonomiyaki. Customers sat at a counter around the griddle and the cook kept up a constant banter with his customers while he prepared their dinners. Convivial is the mot juste for this experience.

Another type of mobile vending is to sell street food from the bed of a pick-up truck. A popular food from such vendors is “takoyaki,” which literally translates to “octopus balls,” and consist of chunks of octopus in a rich batter, fried on a specially constructed griddle that shapes the mixture into round balls, about the size of golf balls. Other vendors offer baked sweet potatoes, which are roasted over an open charcoal fire in the bed of the pickup, or sometimes fresh fruit or vegetables. This is street food in Japan.

My project to visit and photograph all 47 of Japan’s prefectures was rewarding on several levels. This issue of the Monochrome Chronicles featured my experience of local izakaya mostly in small towns. For me, this was a chance to indulge in two of my favorite pastimes, photography and food. Photography in an izakaya presents unique challenges and I’ve been more successful with snapshot pictures, I guess.

In the next episode of the Chronicles I’ll show you another kind of street photography in the prefectures, the open-air morning street markets or “ichiba.”

Addendum

Izakaya are, undoubtedly, a living Japanese tradition. Some are located in traditional old Japanese buildings with traditional interiors. Occasionally, the izakaya has been operated by several generations of the same family in the same location.

Another Japanese tradition is the ryokan or country inn. Genuine original ryokan have largely disappeared but on occasion I stayed in a ryokan during my travels in the 47 prefectures. These two images illustrate the simplicity of design in the rooms of the ryokan though the design may have been slightly modernized.

Another tradition, one that has truly died out and only exists as historic preservation, are samurai residences. Samurai no longer exist, of course, but occasionally I encountered samurai residences, usually as restored historic homes but occasionally as lived-in preserved homes.