Open-air morning markets is a major theme for my photography, a theme that started during my travels in Southeast Asia (see The Monochrome Chronicles #03). The idea of a parallel series with open-air markets in Japan had been percolating in the back of my mind for several years. Such markets used to exist in Tokyo but have gradually disappeared from city life. I finally found Japanese open-air markets during the 47-Prefectures project, which is the theme for this issue of The Chronicles.

Before turning to the photographs, I need to do some context setting. The first item is to introduce the Japanese term “ichiba,” which translates directly to “marketplace” but also carries a considerable amount of invisible connotation. Let me explain. Ichiba refers to an early-morning open-air market that is organized and operated by people in the neighborhood. The vendors, who are mostly women, set up their stalls on the sidewalk in front of their homes. Each vendor tends to specialize in one type of goods – such as vegetables, fruit, fish, flowers and so on – and their customers are people from the neighborhood.

During the later stages of my 47-Prefectures project, and stimulated maybe by publication of my book, “Ichiba: Talad in Southeast Asia,” several Japanese friends asked whether I’d photographed any ichiba in Japan, and why not? My only answer was I didn’t know any Japanese ichiba and had not encountered any in my travels through the prefectures.

Gradually, I began to learn about Japanese ichiba, and found that while such markets had been commonplace at an earlier period of history, slowly they had disappeared from most neighborhoods.

One of the open-air morning markets, Katsuura ichiba in Chiba Prefecture, captured my attention for several reasons. The Katsuura market is touted as one of the three biggest morning markets in Japan, not that the size would be important for my purposes.

The market did not disappoint, though I question the claim about being one of the three biggest in Japan. Some twenty or thirty vendors had their stands set up along a three block stretch of a side street, some with a table or two under a portable tent top and others with their goods spread on a plastic tarp on the street. It is a neighborhood tradition, I believe, for the vendors clearly knew each other and their customers as well.

The goods ranged from fresh fish and fish products to fruits, vegetables and flowers from nearby farms. As I sat and watched, a man and a woman drove up in a pickup. He set up the tent top and she began setting out her produce…cucumbers, only cucumbers and more cucumbers. Before she even finished setting out her cukes, a flock of customers – and other vendors as well – swarmed around her and vigorously snatched them up.

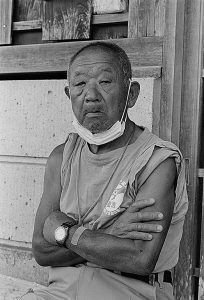

Not surprisingly since Katsuura is a sea port on the Pacific, several of the vendors were selling fish or fish products. The vendors were predominantly women and mostly older women. This man stood out because I could easily imagine him as a fish monger. He acceded to my request to take his photograph but, as his body language shows clearly, he was rather reluctant. As the bottom line, I think, the photograph is a stronger portrait because of his reticence. He tried to look impassive but his inner state of mind shows through.

A more remote market was Yokubo ichiba in Saga Prefecture on Kyushu Island. Kyushu itself, though it is one of the four main islands of the Japanese archipelago, is largely separated from mainstream Japan – and Saga is maybe the most remote prefecture on Kyushu. Yokubo is a small town at the tip of a promontory, with its own harbor on the Japan Sea.

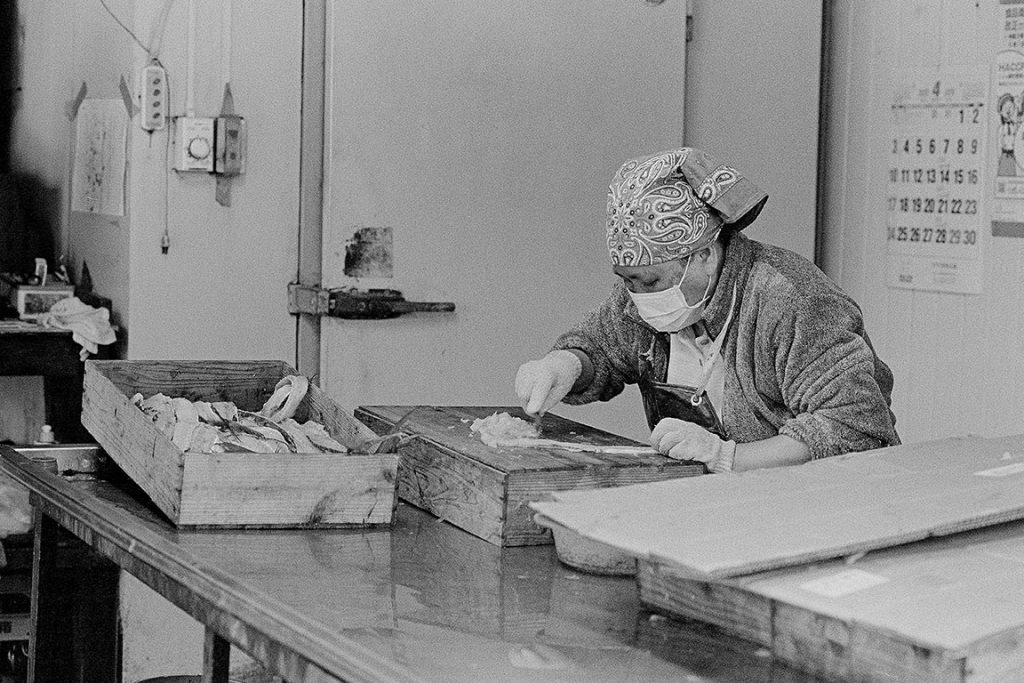

The ichiba itself…well, I wonder whether it wasn’t actually a remnant of an earlier much larger market. A distinctive characteristic was the preponderance of stalls selling squid or squid-related products. In fact, the entire prefecture of Saga is known for squid and squid restaurants. A focal point of the Yokubo Ichiba was a sidewalk cafe where fresh squid and shellfish were grilled on barbeque grills set out on the sidewalk. On the other side of the aisle was a display of fresh squid laid out in the open air to dry. A slow rotary fan above the counter would keep insects away from the squid.

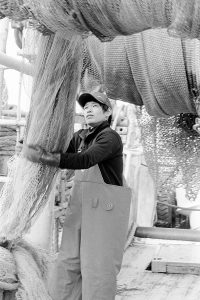

Another of the three famous open-air morning markets was in the small harbor town of Wajima on Noto-hanto, a peninsula on the Japan Sea. The west coast of Noto-hanto, where Wajima is located, is sparsely populated, accessible only by car or infrequent busses. The market, or ichiba, was spread out over several blocks on two intersecting streets. The streets themselves were notable, with wide cobblestone streets (traffic prohibited) lined with vintage Japanese wooden shops. Vendors, mostly older women, had set up their stalls along both sides of the street. The mood was decidedly low key, with vendors chatting quietly with each other and customers walking slowly from one stall to the next, often stopping to chat with vendors. [As a side note, this location was damaged severely by the strong earthquake on New Years Day 2024.]

The atmosphere of this ichiba is portrayed symbolically in this image. If that is an overblown claim, so be it – I’ll stand by it. Some of the vendors’ stalls at Wajima ichiba were more elaborately constructed (though still simple in design). A wooden frame covered with plastic tarp created three walls and extended overhead to form a roof. Fortuitously, this construction yielded a light box suitable for photography.

The main feature of this photograph is the line of fish hanging from a bamboo pole. The uniform size of the fish and their regular arrangement somehow impart a sense of Japanese design, I think. The wooden frame and translucent plastic tarp in the background enhance the overall composition. To me, this image symbolizes the Wajima ichiba.

Segue. These three ichiba – Katsuura, Yokubo and Wajima – were the three traditional morning markets I sought out in the 47 prefectures. Elsewhere were other markets, less traditional, but still distinguishing features of Japanese culture.

This market stall was a unique modern day re-creation of a form of market in historic Tokyo. A simple wooden structure had been built at street level on a side street. Shelves were lined with wooden crates and woven baskets containing fresh vegetables for sale. The price was 100 yen for each package.

And the stall was open 24 hours per day. The owner herself tended the stall during the day. At night she left it unattended. Her produce remained available on an honor basis. Nighttime customers could deposit 100 yen for each package through a slot in the cover of a locked tin container. A unique business model in a upscale neighborhood in modern-day urban Tokyo.

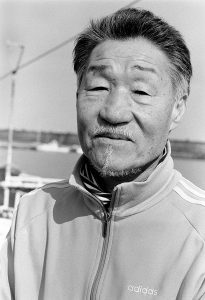

At the other end of the spectrum would be large-scale commercial fish markets. The largest of such fish markets in Japan (and the largest in the world) is in Tokyo, formerly known as Tsukiji Market but recently moved to Toyosu. Far away on the opposite side of Honshu is a smaller but still a rival fish market in Tottori, known as the Marinpia Karo Market. It is on the waterfront of the Japan Sea. Each morning a bell would ring to signal the opening of the market. At the far end of a warehouse, fish would be laid out in rows of styrofoam boxes and a group of maybe 50 or more people gathered around them. The auctioneer, his staff, and the buyers walked from row to row, stopping at each lot for the bidding. The activity was so hectic. To me it looked like pandemonium but surely there was a method.

At the opposite end of Honshu, my camera led me to the Furukawa fish market in the city of Aomori. The market, which covered maybe a half of one city block all under a single roof, was rife with subjects for photography, both the vendors and their produce. The pace was slow and vendors frequently took the time to chat with their customers.

One vendor’s stall caught my attention as much for the colorful display of food items as for the food itself, which included many kinds of sashimi and a variety of Japanese pickles. The pickles added splashes of bright colors to the display. The vendor was an 80+ year-old man, who ran the stall along with his wife who was a few years older still.

Unlike the open-air ichiba, the Furukawa fish market was an indoor facility, though the walls to the sidewalk were open, giving a more outdoor feeling. The vendors operated small individual stands and the produce was virtually all fish and seafood. The market had a community atmosphere, as in this image where the vendor and her customer were engaged in conversation. Admittedly this is a low key photograph but therein it portrays the character of the market.

This episode of The Monochrome Chronicles mainly has featured traditional ichiba in three far-flung locations, but also a few other types of markets. Ichiba was not on my original itinerary when I started the 47-Prefectures project. (In fact, I had no prescribed itinerary when I started.)

The impetus for going to the three ichiba came to me in a backhanded way. At the time when my book “Ichiba in Southeast Asia” was published, Japanese friends asked whether I had been to any ichiba in Japan. I had not. When the COVID pandemic struck in 2020, I still had three destinations still on my itinerary: Saga Prefecture, Boso Peninsula in Chiba Prefecture and Noto Peninsula in Ishikawa Prefecture. By the time I could resume travel domestically in Japan, I had learned about the ichiba in these three locations. In that context, the ichiba were secondary to my goal to visit these three places.

That said, I came to realize that experiencing the ichiba first-hand revealed to me yet another, deeper layer of Japanese culture. This is difficult to describe in words. I think that the key elements are community, ingenuity and tradition. This is my speculation only. Historically, maybe it was ingenuity that first started the practice of ichiba. Then the sense of community perpetuated the existence of ichiba. In the modern era, ichiba have been largely replaced by supermarkets but tradition sustains a few of them in isolated places.

The character of the photographs in this episode is distinctive, diverging a bit from my usual style. A couple of influences are at work here. One factor is that these images come from near the end of the project and my style gradually had become softer during the course of the project. The second factor is deeper and more speculative. All three locations are on the seacoast and I speculate that the atmosphere, and especially the light, is distinctive along the seacoast. If true, these factors must have been at work subconsciously. The bottom line surely was the people at the ichiba, both vendors and customers. I felt that I’d stepped into an earlier period in Japan’s history.

The next episode of The Monochrome Chronicles will feature a mode of train transportation I first experience during the 47-Prefectures project – the so-called one-man densha.