The topic of this, the fifth and final episode based on my 47 Prefectures project, like the previous episode, is train travel but from a decidedly different point of view. Unlike the previous episode, which focused on the trains per se, this episode focuses on other elements of train travel, specifically the passengers, their stories, and the scenery outside the windows of the trains.

This is the final episode about my 47 Prefectures project. It covers three distinct train trips from the point of view of my experiences during these three train trips.

Trains have been my main mode of transportation during the 47 Prefectures project. Riding a train gave me a sense of freedom, and of escape, that I rarely experienced otherwise. Eventually train travel became a theme for my photography. Most of the photographs in this episode are from three specific train trips.

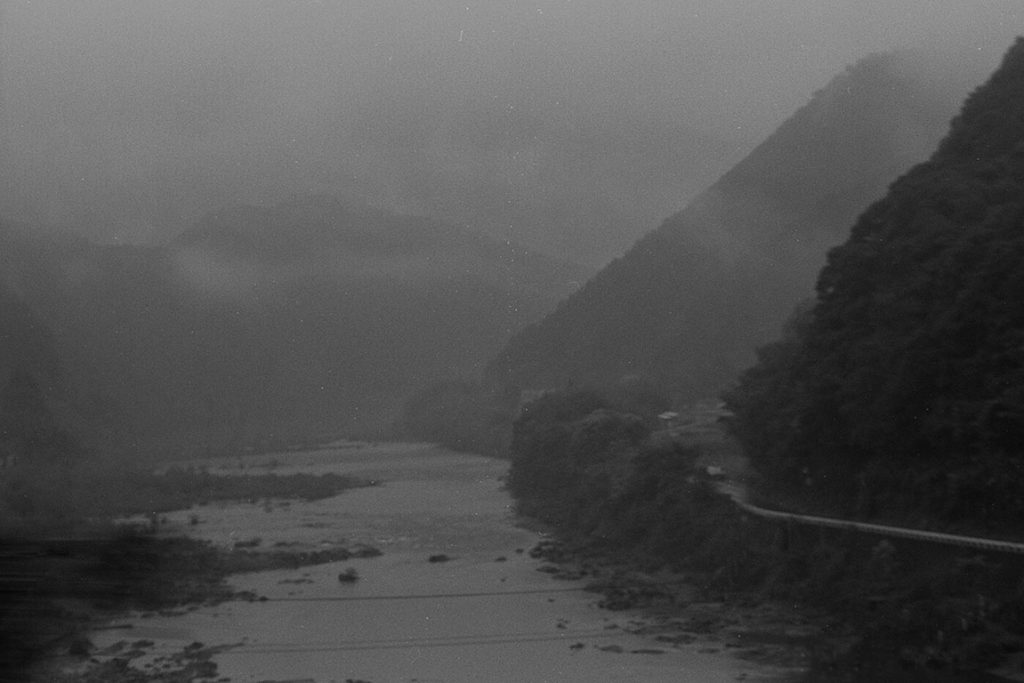

One trip was on the Yodo Line from Uwajima to Kubokawa on the island of Shikoku. This was serendipity. My goal for the day was to travel from Matsuyama in Ehime Prefecture, to the city of Kochi in Kochi Prefecture. In the middle of the day I had to transfer to the Yodo Line, a one-car one-man densha that traveled the inland route through the mountains. That day, the mountains were shrouded in dense fog, which occasionally lifted to reveal the mountains, forests and rivers. The atmosphere of the 2-hour ride was ethereal, a unique experience.

Another trip was from Aomori to Akita along the coast of the Japan Sea in Tohoku, the most northern part of Honshu Island. I rode another one-man densha, the Gono Line along the sea coast, for nearly a full day. The passengers aboard the Gono train, I would like to say, were everyday Japanese folks, local people.

The third trip was, in retrospect, the most ambitious one. Like the Gono Line trip, this one also started in Aomori Prefecture and followed the coastline of Tohoku, but there the similarity ends. This trip was along the Pacific Coast and again I wanted to travel as much as possible by local train. The challenge was that this area of Japan was the site of the greatest devastation from the powerful tsunami after the severe earthquake in 2011. Though 8 years had elapsed by the time of my trip, train service still had not been fully restored in some areas and instead travel was by local bus. My journey from Hachinohe to Sendai, a distance of about 300 km as the crow flies, took 3 days and 2 nights, truly a road less traveled. On the final day I had to detour by bus around the site of the damaged nuclear power plant in Fukushima because the train tracks ran through an area where the radiation level was still prohibitive.

This brief introduction of the three train trips gives the context for this episode. For the next three sections I’ll ignore geography and organize the material by photographic themes: portraits, stories and landscapes.

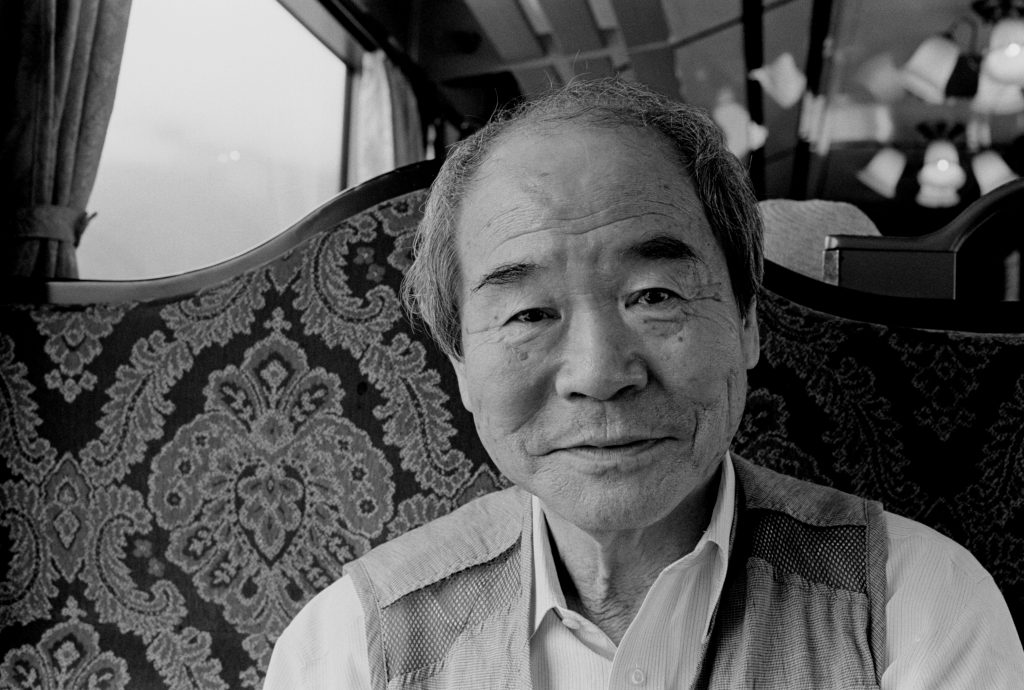

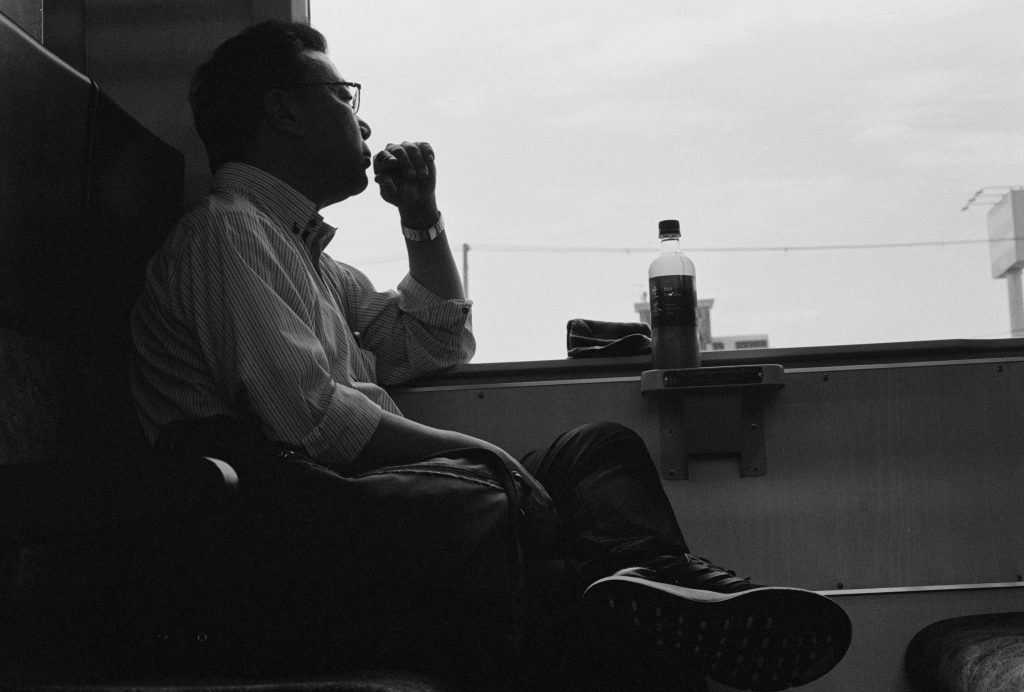

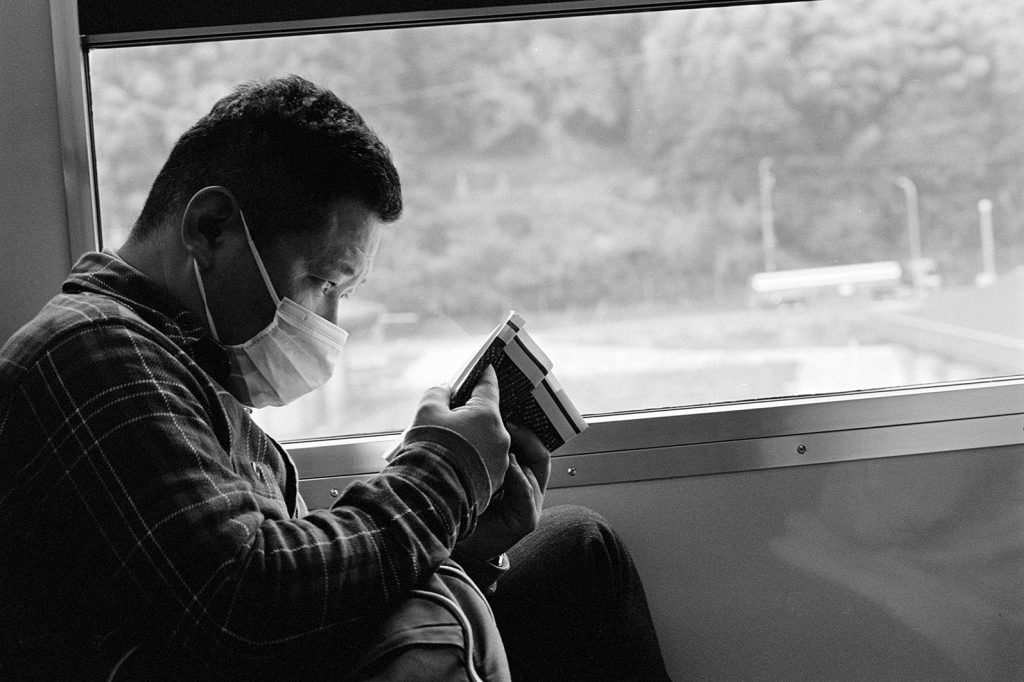

For me, riding the Gono Line along the Japan sea coast was a novel experience that held my attention throughout the journey. For local passengers, on the other hand, it was a routine part of their day and some of them just slept as the dramatic scenery passed by out the windows.

Three views of passengers on the Gono Line but what differences in expression. Photographically, the three images are similar technically – a tad overexposed yet mostly middle gray and soft focus. The differences arise, of course, from the expressions of the subjects. From that perspective, each image is unique. The only thing I needed to do was watch and wait.

Segue to short stories. Next the scene in my camera’s viewfinder switches from passengers on the train to scenes from short stories. One tenet of my philosophy about photography is that each image should tell a story. The corollary is that, as the photographer, I should not tell my version of the story. I amassed many stories during this project. Here are some photographs that tell their own stories.

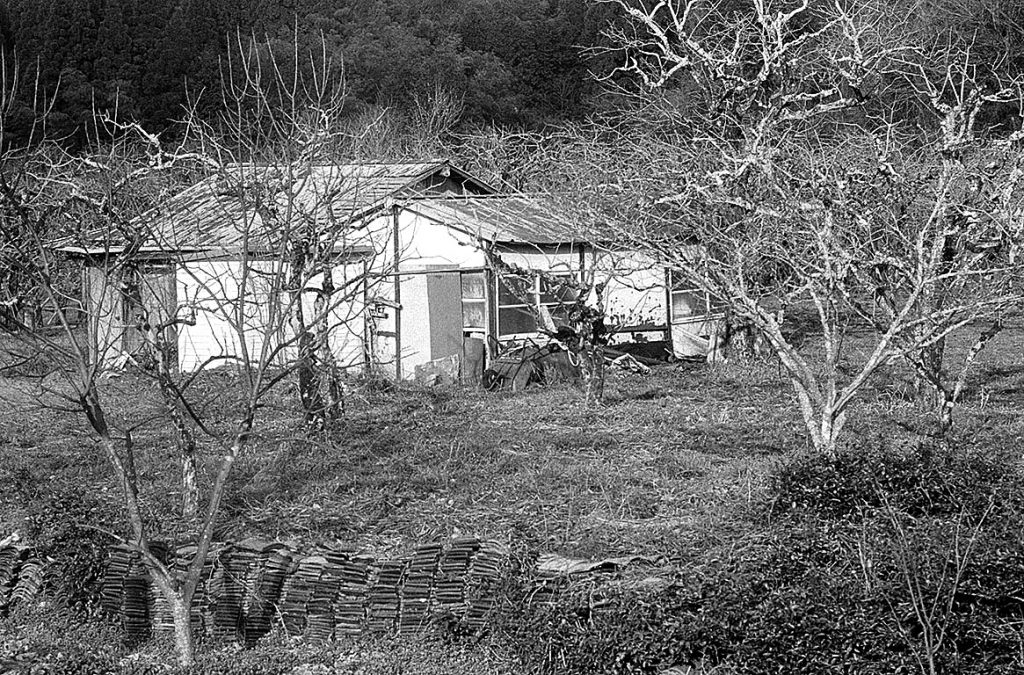

Through the window of a moving train is hardly an ideal condition for taking photographs. Also, the train stops usually are brief and the views there are rather limited. This was an exception. A brief stop, yes, and I happened to be standing by the door when it opened to reveal this view of a farm yard with two oba-sans (aunties) working in the field. I didn’t have to think, I just aimed my camera and fired off a few frames before the door closed again. A matter of luck, and standing in the right place at the right time, and being ready with my camera, combined to create this nostalgic image. Could this be a flashback to my memories of Iowa?

The next three images tell stories of a very different kind. In reality, they are views from the bus rapid transit (BRT) system that replaced the train service through the area of severe damage from the horrific tsunami of 2011 in northern Tohoku. In that context, these images could be photodocumentary. Taken out of context, though, each one tells another story.

佐々木自動車 (Sasaki Motors) – brings the drama to a more personal level. The damage to the shop is visible, but the loss of lives is indescribable.

Other buildings appeared to be intact or possibly had been repaired or re-built. As a photograph, I think, the key element is the single bird perched on the wire. This solitary bird casts a sadness over the image, perhaps a reminder of the thousands of lives lost (animals as well as humans). My interpretation is the opposite. The bird symbolizes the hope that life will return.

Segue to scenics. In case you haven’t noticed it, let me say that my photography mainly focuses on people – while veering between street photography and portraiture. As for landscape photography, usually I just say that is not my forte. That said, I could hardly take on a venture such as this 47 Prefectures project and simply ignore the landscapes and scenery. During the project I found scenic photographs creeping into the series. This was especially the case during the three train trips that form the basis of this episode.

As such, let me deviate from my usual practice and include some of my scenic photographs. It occurs to me that, rather than images that show the scenery, they are more images that show my reaction to the scenery, my state of mind at the moment. Or to put it another way, rather than thinking, “This would be a good scenic photograph,” I would listen to my little inner voice telling me, “Yes, this feels right.” More impressionism and less photorealism.

A very moody scenic image. Several elements contribute to the mood. Fog in the mountains predominates in the background. The gray scale is largely compressed, making the image more intimate. The human elements – railroad tracks, a fence, a road, buildings – almost seem to fade from view. The photograph imparts a calm feeling.

This seascape is unusual with a broad expanse of sea in the foreground, which focuses attention on the small island on the horizon. For some reason the island is what garners my imagination. The predominance of the lower end of the gray scale sets the mood. Marineliner, Shikoku, 2016

Fog was the main theme of my ride on the Yodo Line one-man densha. The fog did abate at times and appears only in the background in this image. Photographs of railroad tracks receding in the distance…well, let me claim that this one departs from the cliché, I think. I’m a little unsure how this is, but the slanting electric poles by the crossing contribute a feeling of something unbalanced. The effect is subtle but intriguing. Then, too, this is a view of the backyard of a remote prefecture. Yodo Line, 2016

Train platforms are a recurring setting in my venture through the prefectures. For this image, a recent rain transformed the scene. Another factor is that on the platform I could take the time to set up the composition within the frame – unlike when I was shooting from the window of a moving train. In this instance, the rain on the cement platform created a more dynamic image. Maizuru Line, 2018

During the course of my journey through the prefectures, the scenery moved from simply being the background in my photographs, and occasionally became the subject per se. This wasn’t a conscious choice but rather a subliminal adjustment of my perspective. Actually, I can’t claim to practice landscape photography but instead I want to convey the impression of landscape as seen through the train windows. A critic might note potential flaws in these images but to me the so-called flaws actually contribute to the impression of landscape as seen through the window of a moving train. My impression…

In this image, the roles of the scenery and the window are reversed. The subject is the window. I prefer to think of this as an abstract image. Though the negative is in focus, the positive image seems to lack detail, an optical illusion of sorts. For me, the abstract expression is the subconscious perception of the window. The conscious mind says the focus should be on the scenery but my little voice says otherwise. Choshi electric railroad, 2019

The next few images are, unabashedly, outside the theme of this episode of The Monochrome Chronicles. Outside, that is, because none of them is from the three train trips that are the focus of this episode and, furthermore, none of them was taken from the train. These photographs are, without doubt, within the scope of my project. Aesthetically they mesh with the rest of the images in the episode.

This image is a departure from the rest of the scenic photographs in this section. The idea for such an image had lived for a long time in my subconscious. Noto Peninsula, 2021

Well, that’s my gallery of portraits, stories and scenics, mostly from these three special train trips. As you can see from this and the other episodes in this 47-Prefectures series, people are the main subjects in my photography.

Now it is time to adjust my viewfinder and zero in on the three train trips per se. No need to worry, I won’t bore you with a travelogue (…first I went there and saw that, then I went…). Among the many train rides I’ve taken during this project, these three stand out in my memory.

Train ride from Uwajima to Kubogawa. Words fail me when I think of my train trip from Uwajima to Kubogawa on the island of Shikoku. Maybe these images will give some impression of the experience. A little olive-drab green one-man densha carried me through fog, mist, and rain, through forests, mountains, and valleys, and alongside a river. I felt completely isolated from the rest of the world – partly because at times the train car was completely enshrouded in fog so thick that the view from the windows was completely white in all directions. I felt like I was in a cocoon floating through space.

Inside, the car had pale yellow walls, grey linoleum on the floor, and dark green upholstery on the seats. All muted colors. The seats were actually just benches along both sides of the car, leaving a wide open space in the middle of the car. Passengers were few that day, maybe ten people or so. The only sounds came from the train itself – the clackety-clack of the wheels, the occasional creaking of the car when it rounded a curve. Occasionally the driver would blow the horn or ring the bell. All these elements combined to make the atmosphere other-worldly, especially when we were engulfed in fog or went through a tunnel.

Travel through tsunami-devastated Tohoku. For some time, I hesitated to venture to the prefectures on the Pacific Ocean side of Tohoku – Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima. These prefectures suffered severe damage from the powerful earthquake and devastating tsunami in 2011 and the ensuing disaster at the nuclear power plant in Fukushima. Several years had passed by the time I began considering going there but still I was unsure whether train service had been completely restored, especially as I planned to use local trains rather than the shinkansen.

When I went to buy the tickets, the agent took a long time to determine the actual route from Hachinohe city at the northern tip of Honshu and along the coast through the three prefectures. Only after I had completed the trip did I understand why it took him so long to issue the tickets. Several local train lines operated in this area so I would have to transfer from one local line to another five times. In addition, I would have to take a bus detour three times because the railroad tracks still had not been restored in some areas.

The final hurdle would be to bypass the site of the nuclear powerplant in Fukushima – by means of a special bus. The through railroad tracks were still off limits due to radioactivity contamination, even 8 years after the accident.

By the way, the train time from Hachinohe to Iwaki city by shinkansen would have been around 5 hours. As I wanted to traverse along the coastline and travel by local train as much as possible, my trip took about 15 hours over the course of 3 days.

Hachinohe to Miyako. During the first leg of the trip, from Hachinohe in Aomori Prefecture to Miyako, Iwate Prefecture, the scenery was shrouded in fog. Fog makes for moody, emotionally dense images in black-and-white film. The Pacific Ocean appeared through the fog occasionally. In a way, these are not spectacular scenes but that is the strength of the images (or is that an oxymoron?). Later I learned that this was not just fog, but fog mixed with steam rising from the ground, a fairly common occurrence in this area. In some recently tilled fields, I could see steam rising visibly from the ground.

Elsewhere the train passed through farm country. Compared to other images of dramatic scenery such as seascapes or mountains, this image of a crop field under a cloudy sky seems understated. That is the point. One of my goals for the project was to see the backyards of Japan.

BRT bus routes. “I had to transfer in Sakari to continue on to Kesennuma. I was surprised to find the transfer was to a special bus (called BRT, or bus rapid transit). Clearly this took us through some of the most badly damaged areas of the tsunami disaster. A lot of huge reconstruction projects were still ongoing, rebuilding the infrastructure I guess. It was awesome and also very sad. The enormity of the damage was evident. The forests, though, were thick and green. I wondered whether the trees had recovered or the area had been reforested.” From my travel log, 2019

These special bus routes were created as adaptation to the horrendous damage from the tsunami. The disconnect between the ongoing reconstruction in the territory outside the bus, and the everyday experience of the passengers inside the bus, was striking. Though 8 years had elapsed since the tsunami, from the extent of the reconstruction and the fact that it was still ongoing, the enormity of the damage was clear. The bus route included local streets in some places, so my point of view was much closer to the damage. The survivors, however, had adapted to a new version of daily life, like taking the bus to go shopping, or to visit a friend, or any of the other activities of daily life.

“The day started with a 2-hr bus trip from Kesennuma to Yanaizu. Apparently, or obviously, the train tracks have not yet been replaced after the 2011 tsunami disaster so the buses run instead. In some sections, the former train route has been made into a single-lane road exclusively for the BRT buses, elsewhere the buses travel on regular highways and streets. Similar to yesterday’s bus trip, this area is very actively undergoing reconstruction. Signs along the way read, ‘Past tsunami inundation area start’ or ‘…end’ showing how vast an area was affected.” From my travel log, 2019

Bypass of Fukushima power plant. Public transportation from Sendai to Iwaki by local train was still disrupted 8 years after the incident in the power plant. Buses would carry passengers from Namie Station to Tomioka Station (a distance of about 20 km) to bypass the contaminated area.

“All-in-all the trip from Sendai to Iwaki went smoothly despite all my uncertainty about it. I had to catch the 8:13 AM train but no problem getting up so early. On the platform before boarding the train I asked two trainmen why the detour by bus was necessary. It’s due to contamination by radioactivity from the Fukushima incident at the nuclear powerplant in 2011, as I had expected. So, four trains and one 30-minute bus ride between Sendai and Iwaki, a distance of about 150 km.” From my travel log, 2019

In retrospect, I realize that my objective of traveling along the Pacific Coast of Tohoku by local train was maybe an ambitious undertaking but very satisfying to me as a photographer. The one-man densha progressed slowly as they snaked along the coastline. Even the several transfers from one local line to the next were rich sources for photography, a chance to see small rural stations. Staying overnight in small towns, seeing the progress of reconstruction after the tsunami, and by-passing the damaged nuclear power plant, all these experiences became fodder for my camera. I want to go back again.

The Gono Line train. Another unique train journey, again in Tohoku but this time on the Japan Sea coast, took me to the prefectures of Aomori and Akita, two of the northernmost prefectures on the main island of Honshu. Not coincidentally, I opted to take a local one-man densha for this trip. One of the secondary goals of my project was to circumnavigate Japan’s main island, Honshu, as much as possible by local trains.

Two different routes are available to go by train from Aomori city to Akita city. The semi-rapid Ou Honsen Line travels inland through the mountains and reaches Akita in about 3 hours. The alternative is a local train known as the Gono Line, which travels along the coast of the Japan Sea and through an area designated as a “Quasi National Park.” The Gono Line makes the trip in some over 7½ hours. I chose the Gono Line. The next step was to convince the agent at the train station that, yes, I wanted to take the slower of the two lines. I guess he assumed that, as I was a foreigner, I would prefer the faster route. At the end of the day, the wealth of subjects for my camera proved that I’d made the right choice.

From my travel log: “I went to the train station [in Aomori] an hour before departure time which was fortunate because it took nearly an hour to find out that the ticket I’d bought in Tokyo wasn’t valid on the train I wanted to take. First I went to the JR station counter. The clerk spoke with such a heavy Aomori dialect that I could hardly understand him except that finally, after much back-and-forth, I came to guess that my ticket was not valid for the seacoast line (Gono Line) and I’d have to exchange it at the View ticket office.

“The upshot was that I boarded the local train in Aomori at 10:00AM and arrived in Akita at 5:30PM. The trip was actually enjoyable though I had to transfer trains three times, including a 1½ hr stop in Fukaura just about lunchtime. Riding on a local train relaxes me and the Japan Sea coastline is beautiful and, in some places, spectacular (in an understated way; oxymoron?).”

The Gono train proved to be a no-frills ride; old cars from a bygone era, wooden seats with thin padding, the clanking of the wheels on the track, the sound of the train whistle, and the swaying of the cars. This was a 2-car one-man densha. It made a total of 43 local stops between Aomori and Akita, a distance of 150 km. I’m sure I was the only gaijin (foreigner) on the train.

The coastline of the Japan Sea in this part of Tohoku is rocky and rugged in places, which makes for dramatic black-and-white photographs. The train stopped in the small town of Fukaura for an hour and a half just about noon, allowing passengers to get out, stretch their legs, and have lunch at a nearby restaurant.

Riding the Gono Train definitely was an off-the-beaten-path journey, a back-porch view of Aomori and Akita Prefectures. The day passed quickly despite the long hours and my camera stayed keenly active throughout. I’m sure it was more enjoyable than the rapid express train would have been.

Collectively, the Yodo Line train in Shikoku, the Gono Line train on the west coast of Tohoku, and the multiple trains on the Pacific coast of Tohoku, form a bridge between me and the backyards of Japan. Trains were the basic mode of transportation throughout my 47-Prefectures project but these three trips stand out in my memory for having revealed to me a side of Japan rarely seen by outsiders. Such was one of my goals for this photographic venture.