OK, this is the premier issue of The Monochrome Chronicles. I suppose I should introduce myself first, then tell a bit about the goals of the Chronicles, and then start at the beginning. Or wait, how can “the beginning” be the third part? It will become clear eventually.

I am a photographer, an avid amateur devotee of black-and-white film photography. I started by taking night and week-end courses more than 25 years ago at the International Center for Photography (ICP) in New York, where I lived at the time.

I have never stopped pursuing photography since then. To date I’ve held 11 solo exhibits in Tokyo, where I now live, and just published my first book of photographs, “Talad in Southeast Asia” (Tosei-sha Publishers, Tokyo, 2021).

Enough about me, now let me introduce The Monochrome Chronicles. By this time in my avocation, I have accumulated an abundance of experience – not to mention a closet full of negatives and a bookcase full of archival prints – and the Chronicles will be a vehicle for me to write about some of these experiences. What a luxury, to be both writer and editor, to have the freedom to include or omit the topics for each issue.

Now a few words about the format and content of the articles. I intend to write about a single topic in each article, using my own photographs as the basis for the narrative. My goal is to keep the articles short enough to take only about 10 minutes to read. My by-line might be “The 10-Minute Episodes.”

My plan is to upload the articles one at a time, at intervals, to my website (www.djhinman.com). Think of this as my “non-blog” as I will be focusing mostly on my past experience rather than the present. (Do you dislike the term “blog” as much as I do? It sounds like the gunk that collects in the water pipes and clogs up the drain in the kitchen sink.)

And the overall organization of the Chronicles? That depends. (I often say that “depends” is my favorite Japanese word.) It depends on many factors, known and unknown. I will be organizing the series as I go along. One advantage of this series is that I can proceed without a fixed agenda.

In the first paragraph, I wrote that I would “start at the beginning” but who is to say where was my beginning? As a baseline, and maybe establish my credentials as a photographer and as the editor for The Monochrome Chronicles, let me show you a bird’s eye view of where photography has lead me over the last 25+ years.

At times my journey through photography has felt like looking through a kaleidoscope and at other times it seemed like riding a juggernaut. My camera would lead and I would follow, heeding my little inner voice. Herein is an array of the best of the best, one for each of my years behind the camera.

Psychology teaches that the best predictor of what will happen in the future is what has happened in the past. That viewpoint is suitable in areas such as science and technology, where I spent most of my working life. Unfortunately, such a perspective stifles creativity and discourages innovation. I had to learn a new viewpoint for my photography.

At first, while I was taking night courses, ICP introduced me to various approaches to photography such as documentary, portraiture, photojournalism, street photography and so on. Briefly, I dabbled in each one, rejecting one after another rather like Goldilocks, trying to find my comfort zone.

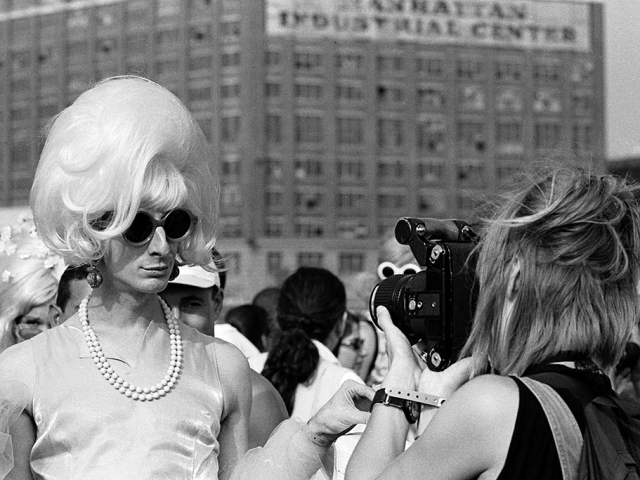

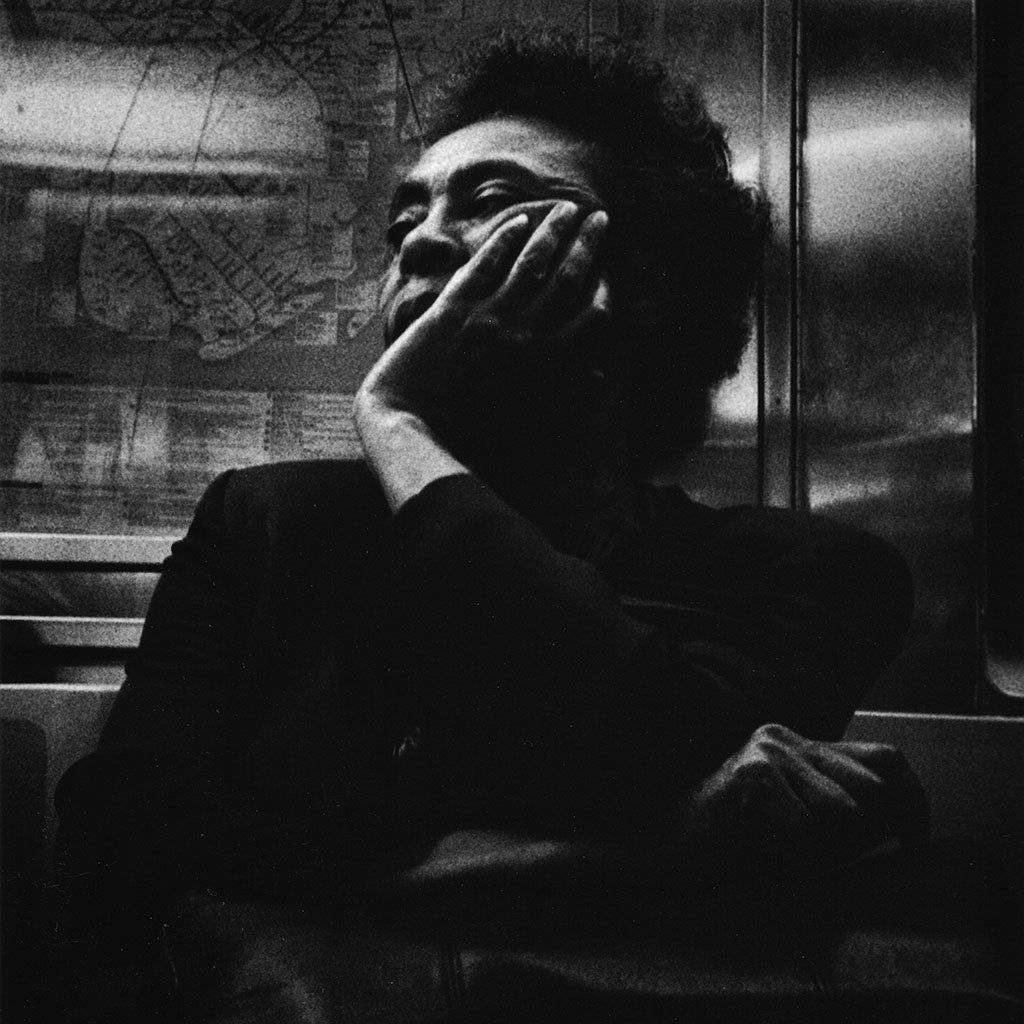

I gravitated to the street photography by leading figures such as Lee Friedlander, Gary Winogrand, Helen Levitt, Diane Arbus, the list goes on. In time I discovered Weegee (Arthur Fellig), who quickly became my favorite street photographer. Not surprisingly, my early attempts at street photography tended to follow in their footsteps.

Eventually, though, I began to develop my own point of view. NYC offered a vast array of subjects. Such subjects as Chinatown, the subways, and a festival of drag known as Wigstock drew my attention.

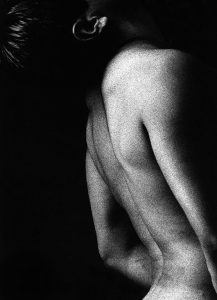

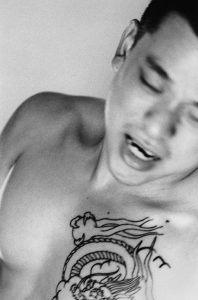

Urged on by my mentors at ICP I began to experiment with more personal subjects. This led, in a round-about way, to my work photographing the male nude.

Photography of the male nude is a crowded field with early works by George Platt Lynes and more recent work by Robert Mapplethorpe and Herb Ritts to mention just a few. As a gay man I was drawn to these photographs. As a photographer, well it was a different story. At first, the male nude was the subject for my photography but in time my point of view morphed into a different direction. The men themselves became my subject, and nudity became secondary. My style veered toward portraiture of the male nude. This work started and came to fruition while I was still living in New York, and has continued after I moved to Japan.

During this period an extreme event occurred in NYC – the attack on the World Trade Center on 9/11/2000 – which radically changed my approach to photography. I lived in the West Village, practically within the shadow of the twin towers, which had been visible from my apartment window.

Two days after the attack, I began to carry a camera with me every day, usually just a small point-and-shoot. I still do. Why? The events and the aftermath of 9/11 made me value each day thereafter. It seems cliché to say, but I began to “live each day as if it were my last.” I would look around me wherever I went, to focus on the immediate. My original goal was to carry my camera every day for a year after the attack. It turned into a life-long practice.

Needless to say, moving to Tokyo in 2003 forced a major shift in my photography. Initially, I continued to pursue street photography much like I had done in NYC, with one big difference. In NYC I was shooting on streets that I already knew from living there for some 25 years and street photography was a means of expression about my experience. In Tokyo, on the other hand, the streets were new territory for me so street photography became a means of exploration rather than a means of expression.

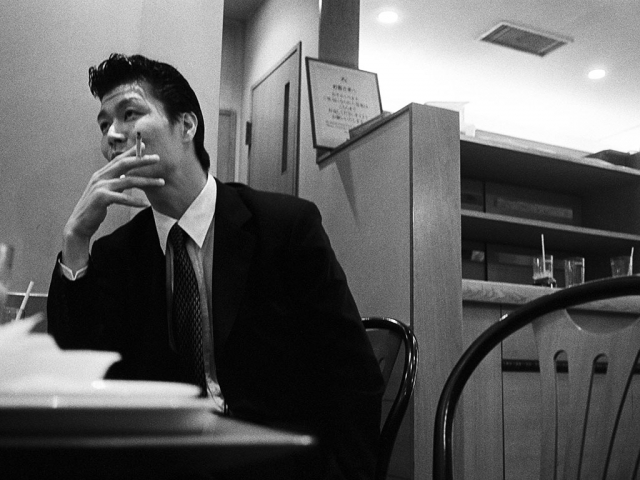

As a major departure, about 2005 I began a series about the Japanese salaryman, initially with a street photography approach but the series veered toward documentary. This work was a main focus for my photography for some three or four years. The series was divided roughly into three themes: the salaryman commuting to and from the office on the train; nomikai, or drinking sessions in the bars after work with colleagues; and the mad dash to catch the last train home at 1:00AM on Friday night, or failing that, staggering onto the first train home at 5:00AM on Saturday morning.

Another series was an extended portrait of a homeless man. No, let me correct that. An extended portrait of a man who happened to be homeless. This, too, was a fusion between street photography and portraiture. I encountered this man occasionally over a period of about 4 years near the darkroom where I did my printing.

In my early years in Japan, I became enamored of a kind of street festival known as matsuri, a mix of religion and secularism with a history reaching back hundreds of years. Street photography and matsuri are a natural match, which I pursued for several years. This lead unexpectedly to a long-term ongoing series centered on one gang of yakuza, the so-called Japanese mafia – for me an unconventional series and one that is close to my chest.

After I moved to Tokyo, I made a conscious decision to spend my leisure time in Japan and other countries in East Asia. My camera traveled with me, of course.

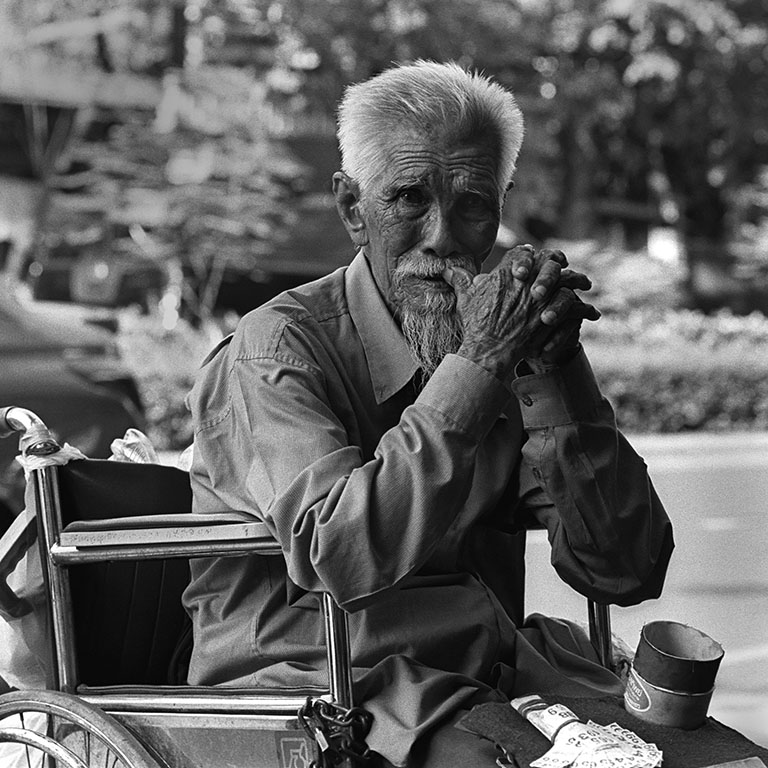

Street photography was my initial approach wherever I went, using it as a vehicle for exploration much as I had done in my early years in Tokyo. Needless to say, the streets of such major cities as Bangkok, Saigon, Hanoi, Siam Reap, Yangon, and on and on, offered seemingly infinite material for street photography.

One hurdle was to get past my antipathy about going to Vietnam. As a university student in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the war in Vietnam was a daily presence in the newspapers and television news, and the draft was a threat hanging over the campus. For years I avoided anything to do with Vietnam. Finally in 2005 a trip to Saigon managed to excoriate some old ghosts.

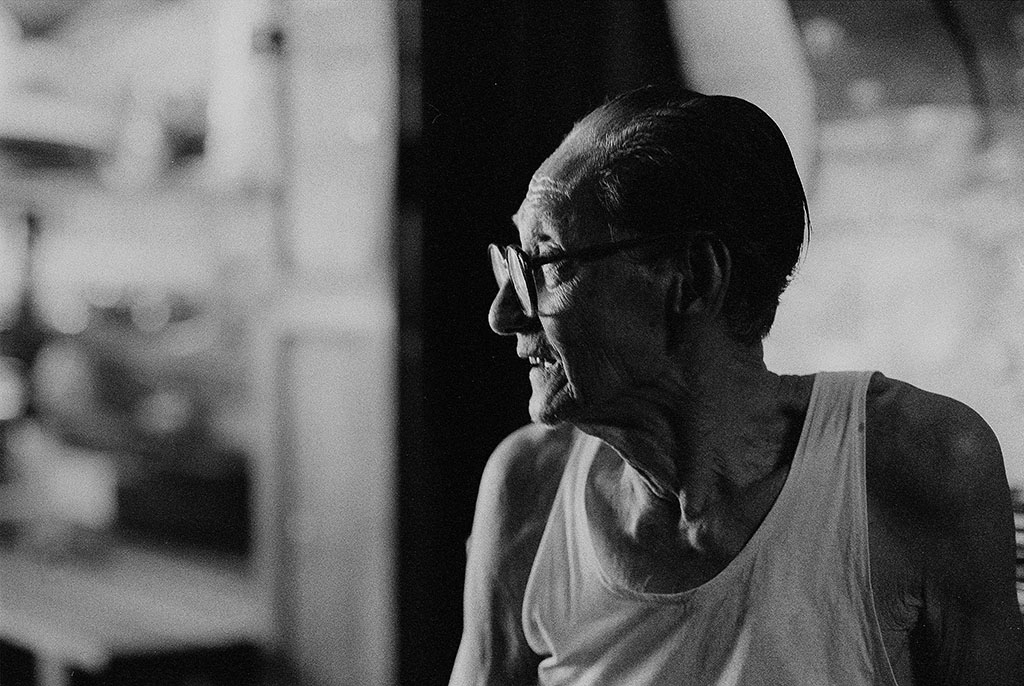

Gradually, though, portraiture became my predominant medium, somewhat to my surprise because without my camera I tend to be awkward with strangers. My camera and my little inner voice guide me here. My extended portrait of this man, a denizen of Silom Road in Bangkok, covered a total of 11 years.

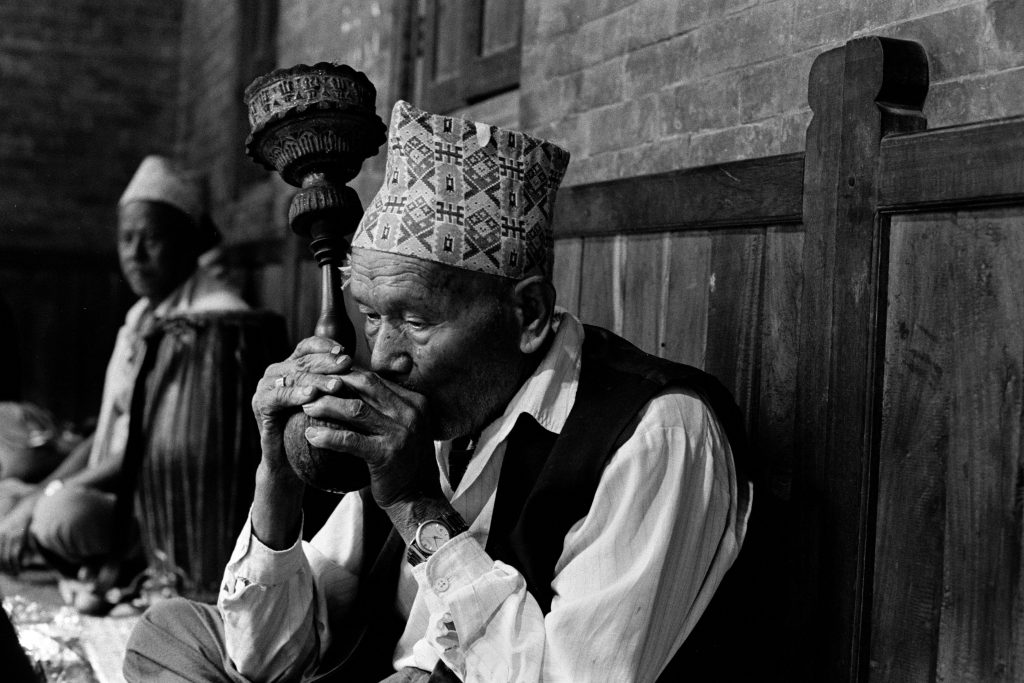

Mongolia was a turning point in my ventures in East Asia. Usually my destinations tended to be large cities, but in Mongolia I travelled far off the beaten path into the central highlands, home to many nomads. Sleeping on a cot in a ger under a vast sky, and reveling in the immense quiet, I re-set my goals and began searching for small rural villages.

Farther, much farther off the beaten path than I could have imagined when I started my journey of discovery through photography more than 25 years ago back in NYC.

Now, why do I take photographs? For me, photography is a visual diary. I carry a camera every day, wherever I go. Often, I do not have a clear goal, but rather I just wait until something grabs my imagination. These photographs are proof of my existence. The philosopher René Descartes said, “I think, therefore I am.” For me, I take photographs, therefore I am.

To get back to the issue of starting at the beginning, I wonder how far back that would be. I am reminded of a story about a well-known photographer – possibly Garry Winogrand – who once said in answer to a question from his audience something like, “You asked me how long did it take me to make this photograph? I have two answers. The first is, ‘1/60 of a second.’ The second is, ‘My entire life time up until I pressed the shutter.’” In that sense, I would have to start many, many years ago.

As a starting point, imagine me as a boy growing up on a farm in Iowa in the 1950s. This was the baby boomer era: Eisenhower in the White House, a car in every garage and a chicken in every pot. On the outside, at least, I grew up as a sort of a milk-toast: white, bland, flat. Fast forward to 2022 and find that the boy has lived in two major cities; has journeyed so far; has met so many people. A small part of me wants to ask, “How is it that an Iowa farm boy could have all these adventures in NYC and in Asia?”

The answer is that, after entering the university (affectionately known as the “cow college”), several turning points laid the groundwork for my entry into the world of black-and-white photography. They spanned a period of nearly thirty years and, I must admit, they occurred without any conscious design from me. These things just happened.

The first turning point was a summer job I took in 1967, between my first and second year at university, operating a combine as a migrant worker on the wheat harvest on the so-called Great Plains of the Midwest. With a one-way Greyhound bus ticket, $50 in my pocket, and a change of work clothes in a gym bag, I headed to my destination Gruver, TX, a small town in the Texas panhandle. That summer I slept in a sleeping bag on the ground every night, ate breakfast and supper at local greasy-spoon cafes. When there was no work, which was often, I hung out with my fellow crew members in the small towns, went to a pool hall and beer joint for the first time in my life, and even once to a porno movie house. At the beginning of the summer, I set out with dreams of earning enough money for an entire year at university. I returned at the end of the summer with $100 in my pocket. My dream of earning that much money had vanished. In its place, though, was a wealth of on-the-road experiences that radically changed my perception of life.

By the way, the image in the previous paragraph is not from my summer on the wheat harvest. Taken in 2018 as part of my series about the 47 prefectures of Japan, nonetheless it hints that my experiences back then still somehow influence my photography even today. Subconsciously.

Returning to Iowa was a culture shock. I had learned to challenge expectations and I found I no longer fit into small-town Iowa mentality. My role models had turned to dust. I needed to escape but it would be five years before I finally could flee.

The 19-year old farm boy who boarded that Greyhound bus with $50 and a ticket to Gruver, Texas, in his pocket, he would never have dreamed of living in NYC and Tokyo, and travelling throughout East Asia. The young man who stepped down from the bus on returning to Iowa 81 days later, he was capable of such dreams, though the reality would be delayed some 25 years.

Unlike the summer-long experience as a migrant worker in the wheat harvest, the next turning point occurred over the course of a few hours. And, many years would elapse before I fully realized the meaning of the experience. A spring day during my third year of university. As I walked between classes, suddenly I felt an unaccustomed awareness of my surroundings. I realized that the grass was green, that the weather was warm and the sun was shining. I felt like a veil had lifted and, maybe for the first time, I could see clearly. I had not realized the huge dark cloud that I had been living under. This lifting of the veil of depression that I lived under lasted only a short time, maybe a day or two. The awareness stayed with me, though, and would seep into my consciousness occasionally over the next few years. I would live under that shroud for more than 30 years, however, before I found my way out. The lifting of that cloud, after years of psychotherapy and eventually effective medication, was nearly co-incident with my taking up black-and-white photography. Coincidence or cause-and-effect? I can only say this: that one year I unilaterally decided to stop my medication. And my camera went silent. I resumed the medication and my camera came back alive. Enough said.

Another turning point occurred in 1975, when at the age of 28 years, I stepped off a train and for the first time walked up Seventh Avenue in New York (NYC). I remember that day clearly. Everything before that was prelude. That guy walking up Seventh Avenue, he was the one who would eventually journey to Japan and Asia. Three years later, I found myself living in NYC.

The 25 years I spent living in NYC were a maelstrom of experiences, some good and others not so good, but they did ultimately lead to my enrollment at ICP for night classes and weekend workshops. I moved to NYC in 1978 but didn’t enroll at ICP until 17 years later in 1995 – so obviously a long string of events transpired in the interval.

The primary lesson learned from my years at ICP was, “Shoot from the heart, not from the head.” When I first started the entry level course, such a philosophy would have been anathema to me. A camera is metal and glass. Film is celluloid and silver. A print is paper and silver. These are all solid elements, part of the objective world. Where would “shoot from the heart” enter in? The change in my point of view crept up on me gradually.

Well, enough about me. This has been a bird’s-eye overview of my 25 years behind the camera. Most of the images in this article are from a private series that I call “Two Hundred Best,” an accumulation of what I think is my best work. At the end of each year, I take a week or so to review the year’s contact sheets and select the 12 best photographs therein. Then comes the difficult task of deciding whether any of them deserves a place in the Two Hundred Best series, and if so, which photographs they will replace. In the next issue of The Monochrome Chronicles, I’ll show you more from the 200 Best and discuss them in greater detail.

No galleries to display, yet. Please create a couple of pages and assign this page as its parent page.