In the previous episode of The Monochrome Chronicles, I introduced my series that I call the “Two Hundred Best,” which is the topic of this episode. Let me explain about this series in greater detail. At some point early in my ventures into black-and-white photography, I read an opinion by one of the gurus in the field – it may have been Ansel Adams – that the goal of a good photographer should be to produce 12 outstanding photographs in a year. I picked up the habit and have tried to meet that goal every year.

With time, the 12 best images from each year began to accumulate. I set a goal of creating a series with the best of the best. Each year after selecting the 12 best for the year, I then have to evaluate whether any of them are good enough for the “Two Hundred Best” category and, if so, I have to eliminate an equal number from the total.

Now I suppose this raises the question: What do I mean by “the best”? It is my subjective judgement, based partly on my experience at ICP. The first criterion is high technical quality. The second criterion, the more difficult one, is whether the photograph moves me, simulates me, has emotional impact.

Well, enough about me. The goal of this episode of the Chronicles is to show some of the top photographs from the series. One final comment before proceeding: There is no over-arching organization to the sequence of images in this episode. Take each photograph as a stand-alone. The only commonality is that they all came from my camera. OK, I guess the other commonality is that I selected them for this episode, which shows my point of view.

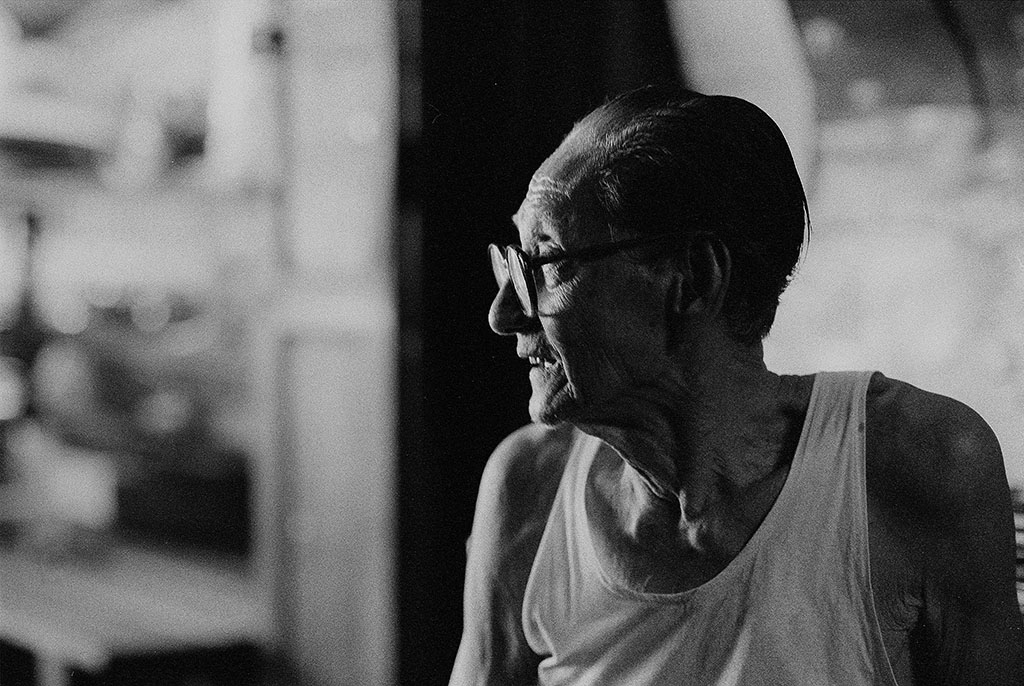

Old Man Lee was one of the vendors at the 100 Years Market in Thailand. He was 70-80 years old and had been making coffee at the same coffee house for more than 60 years. The cafe was a dimly lit, narrow room, with only three or four small tables. Old Man Lee ran the place by himself and prepared the coffee individually on order. He also was very loquacious and enjoyed talking with his customers. Sitting on a table near the entrance were stacks and stacks of ledgers in which his customers had written their names, addresses and comments over the years.

Old Man Lee was unfazed by me and my camera. He went about his work as usual, and chatted with his customers, which allowed me to capture him in a casual, candid mode. Strong side lighting makes this portrait more dramatic. For several years I considered this to be my best-ever photograph, and still remains in the top tier.

Without doubt a determining factor for me was that this was the first time I could spend such a prolonged period of time devoted exclusively to photography morning, noon and night (which rapidly turned into afternoon, evening and night as I stayed out all night following my muse).

Officially, religion was banned in Castro’s communist Cuba. The churches, however, at least some of them, seemed to be well maintained. Curious. The dynamic in this photograph intrigues me, even now more than 20 years later. The scale of the image is unusual for me, with the building taking up most of the frame. My usual point of view is to focus on smaller elements, often close-ups of people. The other element is the contrast between the majestic old church and the figure of the man who seems so small in comparison. A photograph of the church alone might be effective given the unusual illumination. The addition of the man walking by changes a static image into a dynamic image. The high grain of the film contributes to the moody atmosphere.

During the week-long “Silver Week” holiday in 2009, I set a goal to walk at midnight along the entire route of the Yamanote Line train tracks, which encircles the 23 wards of Tokyo. Every night for a week, I walked along successive segments of the train tracks, until I had completed the entire 35-kilometer route. Some neighborhoods were so quiet that it was easy to forget that I was on foot in Tokyo. This photograph comes from that project.

Despite being so busy during the day, this street was vacant at midnight, exuding an eerie ghostly atmosphere. And the street and sidewalks were remarkably clean. This appears to be a distortion of reality. The image seems like a still from some science fiction movie, with the headlights from an outer space vehicle gleaming at the end of the street.

This image is are uncharacteristic for me in the sense that the frame contains a great deal of open space. Possibly this reflects influence of the Japanese style of photography on my work since moving to Japan. The entire frame is filled with the subject in Western photography. The opposite is the trend in Japanese photography where much of the frame is open, allowing the viewer’s imagination to have free rein.

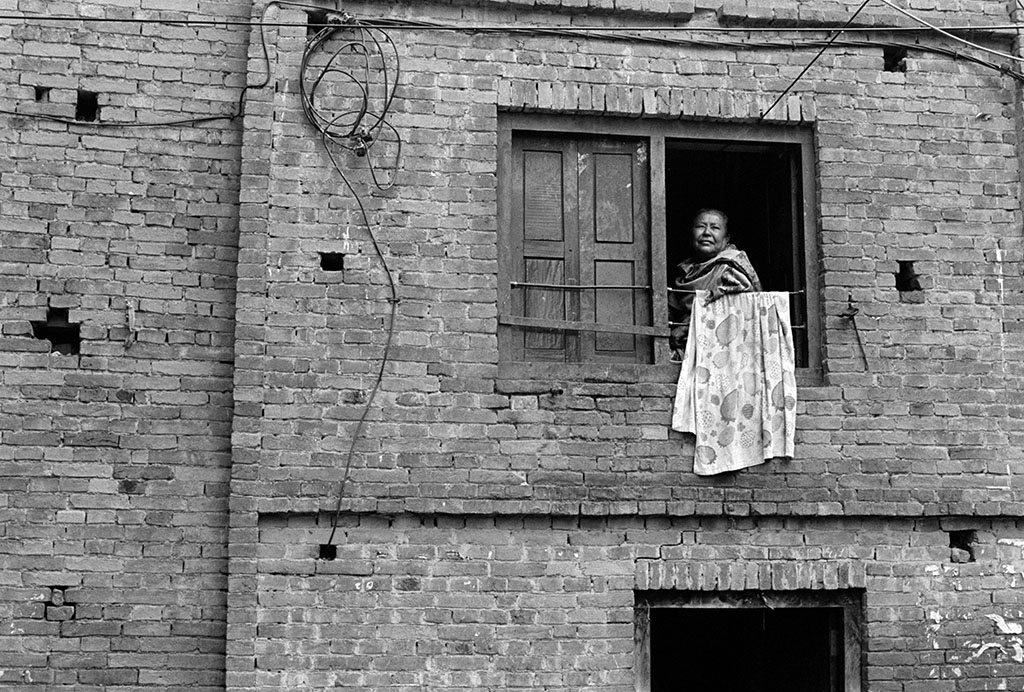

The scene is one of the back streets in Taito ku (Taito ward), near Asakusa, part of Tokyo’s downtown. Though Taito ku technically is part of metropolitan Tokyo, it retains the atmosphere of a small town or village. Here the houses open directly onto the street. No sidewalks. The streets are wide enough for car traffic, yet cars rarely pass through so it is safe to walk along the street. The streets and alleys are neat and orderly. No gaudy advertisement signs or billboards mar the appearance of the neighborhood. Clearly, this woman belongs to the neighborhood.

I’ve captured her indelibly in one moment of time, akin to Cartier-Bresson’s “Decisive Moment” (though my work certainly is not in the same class as his). Many elements coalesce to create such an image. Cartier-Bresson himself described it as being in the right place at the right time, anticipating what will happen, and then waiting to press the shutter at exactly the moment. For me, there is another element: serendipity. The ability to recognize that decisive moment even though it may be totally unexpected. Shoot first and think later.

I spent quite a while at this train station, photographing commuters getting on and off the trains. This frame stands out from all the rest. The light, coming from several sources, complements the scene – no, correct that, the light enlivens the scene. What is the song lyric, “The people ride through a hole in the ground”? OK, this train was above the ground, but still the people were entering the train in a pack. Crowded but orderly, with people still giving each other distance. Only the woman on the left was looking somewhere outside the frame. She was the only woman in the frame.

This is the so-called “nomikai” (literally “drinking meeting”), a time when barriers disappear. When the weather is fair, the izakaya set up tables and chairs on the sidewalks or even in the streets. In this image, the nomikai was over and it was time to go home.

Stereotypes about the Japanese salaryman (the definition has been broadened somewhat to include business women, but the term “salaryman” persists) such as working long hours every night and rowdy uninhibited drinking parties lasting until late in the night. This image shows an atypical view of a Japanese salaryman, when this man was alone and in a pensive mood.

This man made it to the platform at the train station but no farther. The other passenger had turned his back to the situation. Drunks on the platform on Friday night are just part of the usual.

Drunken salarymen have been photographed frequently, to the extent of being practically cliché, so finding a different angle on the subject is a challenge. To pass out on the train platform while still standing is unusual. The moving train in the background adds dimension to the image. The strength of this photograph is its combination of humor and pathos.

Somewhere deep inside a part of me whispers, “There but for the grace of God…” I used to encounter this man occasionally in this same place on the sidewalk in Shinjuku, a neighborhood with many camera stores. Often he would be reading a newspaper or a book.

On seeing this photograph, one viewer asked, “Is he dead?” No, he was just sleeping. The homeless have been the subject of many photojournalism projects, of course, but I feel that this image is different because the man’s face reflects a kind of dignity in repose.

Full body tattoos are part of the yakuza culture, but according to their own code baring their tattoos in public is usually prohibited. Sanja Matsuri, an annual street festival, is an exception.

Beautiful light and strong shadows enliven this photograph. The image breaks the rules of composition but this only adds to the overall impression.

In my mind’s eye, this image works on several levels. This was also an out-of-context situation where the local yakuza gang was hosting a block party on their street. These yakuza let their guard down during the matsuri, mingle freely with the crowd, and willingly pose for foreigners like me and my camera. The body language of these two men reveals hints about the interaction between them.

Taking photographs of yakuza generally is discouraged in Japan, so for me it becomes a kind of forbidden fruit.

This scene is outside of time, or it could be any time. Time has ceased to exist in this scene.

Train travel in Japan is efficient and reliable. Recently during my project to visit all 47 of Japan’s prefectures, I discovered that travel by local trains was more suitable for my purpose which was to seek out the “real” Japan, the off-the-beaten-path Japan. In time I realized another side benefit of riding on local trains. I simply enjoy the ride.

Actually, I see symbolism in this image, the Japanese sense of everything being just so. The train platform and the train car itself were remarkably clean. Ironically, there were no people in the scene, ironic because most train stations in Tokyo are crowded with people. This is ironic for me as well for most of my photographs focus on people. This was just a quick-grab shot from the train window while my train made a brief stop., forever frozen in the negative and print. This photograph is the opposite.

A matsuri is a mix of religious and secular festival, popular in Japan in the summer, featuring a parade of portable shrines or mikoshi. The Shinagawa Tenno matsuri was unique for the Oiran Dochu parade, with women dressed in gorgeous kimono and elaborate hair styles recreating the fashion of Edo-era (1603 – 1868) oiran, or courtesans.

On my second visit to Shinagawa tenno matsuri I was standing near the end of the parade route when one of the oiran performers approached me and introduced herself. This was Tomomi-chan. I saw her again several times during my yearly visits to the tenno matsuri. We spoke together, we traded e-mail addresses, she even introduced me to her mother one evening after the parade. She also came to one of my photo exhibits.

As an aside, the Shinagawa Tenno matsuri has since then discontinued the Oiran Dochu parade, so this photographs documents at custom that no longer exists.

Matsuri are noisy, hectic events so it is remarkable that I could capture a close-up intimate image such as this. Tomomi-chan and I had met previously on several occasions, so this smile was just for me. The photograph could be perilously close to cliché or kitsch, but her eye contact with me and my camera elevates it to a pensive, intimate street portrait.

And the interpretation depends on the mood of the viewer. For example, this was Sunday afternoon and these two women in fancy hats maybe had been to church and were returning home. Or were they on the way to church? My friend Rob was riding the train with me, and he said, motioning to the women, “Now there is a good subject. You should take their picture.” I replied, “I already have.”

The perspective in this image is somewhat unusual, from a low angle looking up at the women. This is due to the technique of “shooting from the hip” with the camera held at waist level, rather than at eye level.

The other element of this photograph is that the two women are so much alike yet so different. Both are wearing their Sunday-going-to-church clothes and hats, but one dressed in white and the other in black. Their body language is similar, both looking at something outside the frame, but one has a slight smile and the other a slight frown.

The real strength of the photograph, I think, is in its ordinariness. It just shows two passengers riding on the subway. And yet the photograph immortalizes a single moment in the lives of these two women.

Iggy created a sensation wherever she went, I think. She never spoke. She walked with a stately carriage, as if she were a model on the runway. Her clothes, too, always were striking. Finally, her make-up was always flawless. All these elements combined to give her a distinct aura.

Opportunities for photographing men in drag abound in NYC: Wigstock, the Gay Pride Parade, Halloween, and the Easter Parade to mention a few. I started photographing drag at Wigstock because it was an opportunity to photograph people close up in NYC without the usual inhibitions about shooting on the streets.

This is perhaps the most striking image of drag that I took in those days. Almost everything in the frame is static, especially her wig and sequined mask, except for the swinging of one ear ring. One viewer commented, “It looks like a Visconti film still.”

Comparison of these two photos, the one of two women riding the subway and the other of Iggy, while the differences are obvious and many, reveals some key elements of my development as a photographer. One was shot from the hip and the other was composed through the viewfinder; for one I used my little point-and-shoot camera and for the other my standard SLR; one image is grainy and the other is in sharp focus; one is casual and one is posed; black vs white. My conclusion from this is that I was still experimenting with various styles during that period. My other observation is that over the years I have incorporated these diverse elements into my own personal style of photography.

As I said in the introduction, the photographs in this episode have no all-encompassing theme, so please take each one individually. The transition from the previous image of Iggy in NYC to the next image might be awkward, so just allow me to break up the narrative at this point. The two images are, after all, separated in time by 20 years and by more than 7500 miles geographically, not to mention the seismic differences in culture. Just so you know…

This image illustrates the effect of the sunlight at dusk. Much of the image is in shadow but the woman’s face is bathed in a delicate warm glow. The soft focus adds to the overall mood of the photograph.

Without doubt, portraiture is a strong element of my photography. I prefer to think of this as a street portrait, the result of a brief encounter with this woman who was at work. She continued working while I was taking the photograph, which allowed her true being to illuminate the image. It is a haunting portrait.

She was sitting in just this pose when I first saw her. She turned her eyes to look at me briefly, acknowledged my camera, then turned her eyes back into this pose.

Well, when I said I didn’t have to do anything, still I had to be ready when my little voice spoke to me. The resulting image has a haunting beauty that is tinged with sadness. Its strength is in its ordinariness.

I will say that this is another “I almost missed it” moment. I had passed by, deep in conversation with my friend, when I stopped and went back. Read into that whatever you wish. One of the lessons learned from my mentors at ICP is that a successful photograph is 80% technique, 5% perspiration, 5% inspiration, 5% location, and 5% sheer luck. I know which element created this image.

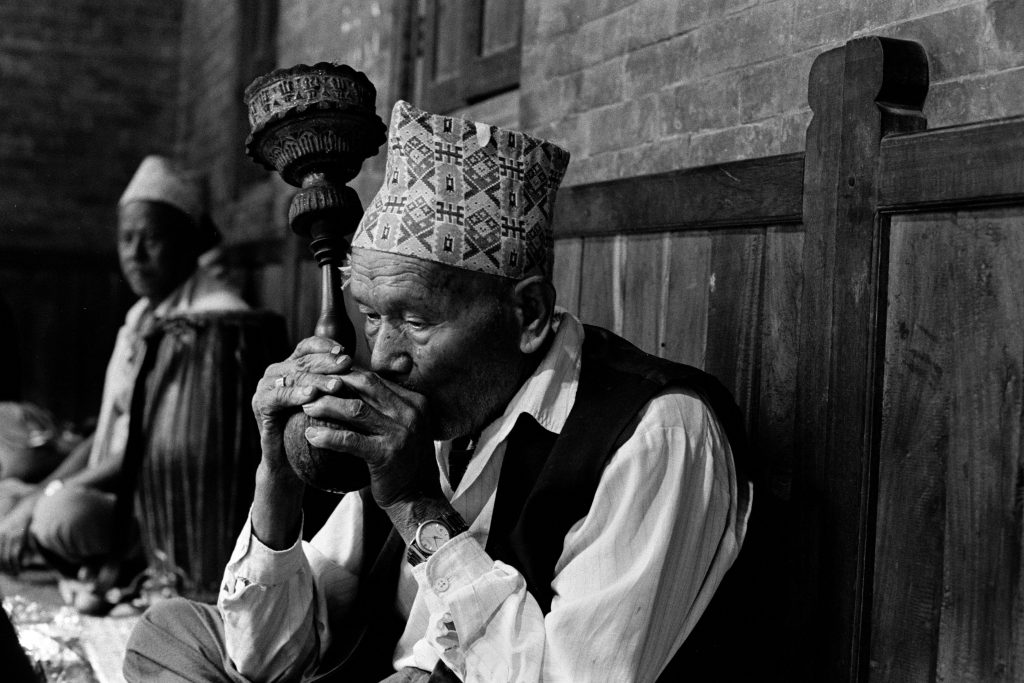

The old section of Bhaktapur, Nepal, is a busy place in the morning. The morning market fills the main square and spills over onto the side streets.

Motorbike drivers beep their horns as they thread through the crowd. Worshipers at the temples ring the brass bells as part of their prayers. Neighbors stop to chat and share a glass of milk tea. Children, dogs, and sometimes goats run about and play in the streets. One morning, seeking respite from all the cacophony, I ducked into an alcove in a building on one of the side streets. I could enjoy the quiet. Then I noticed these two women across the narrow street. It was an opportunity I could not ignore. I needed no help from my little voice this time.

This image comes from deep down inside; I don’t know exactly where. The light and the shadows; the background and the foreground; the women’s clothing, their body language and, most importantly, the expressions on their faces; everything coalesced. This was their moment. The composition may look staged but it is not. Everything is as I found it. I was almost afraid to move lest I disturb them. This portrait belongs entirely to the two women.

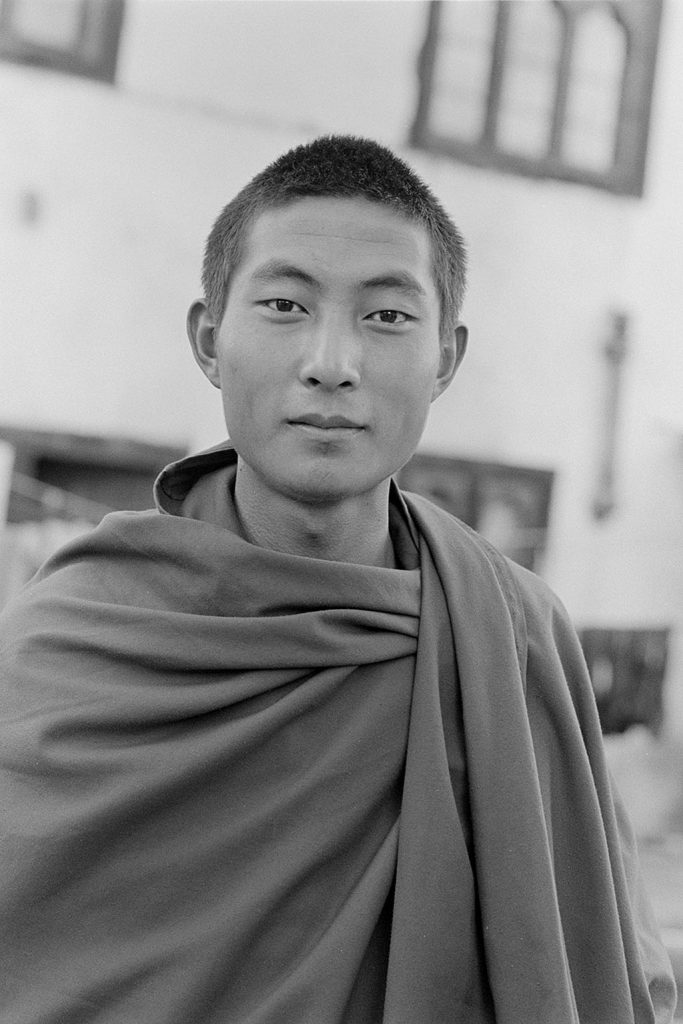

After relocating from NYC to Tokyo in 2003, I have spent a lot of time in Southeast Asia and countries in East Asia. Just what draws me and my camera to these destinations would be tricky to explain. Luckily, I don’t have to explain, I can let the photographs explain. Certainly, the many people I’ve met and photographed has been a major factor. My motivation is deeper than that but, as I said, I forbear to explain it in words.

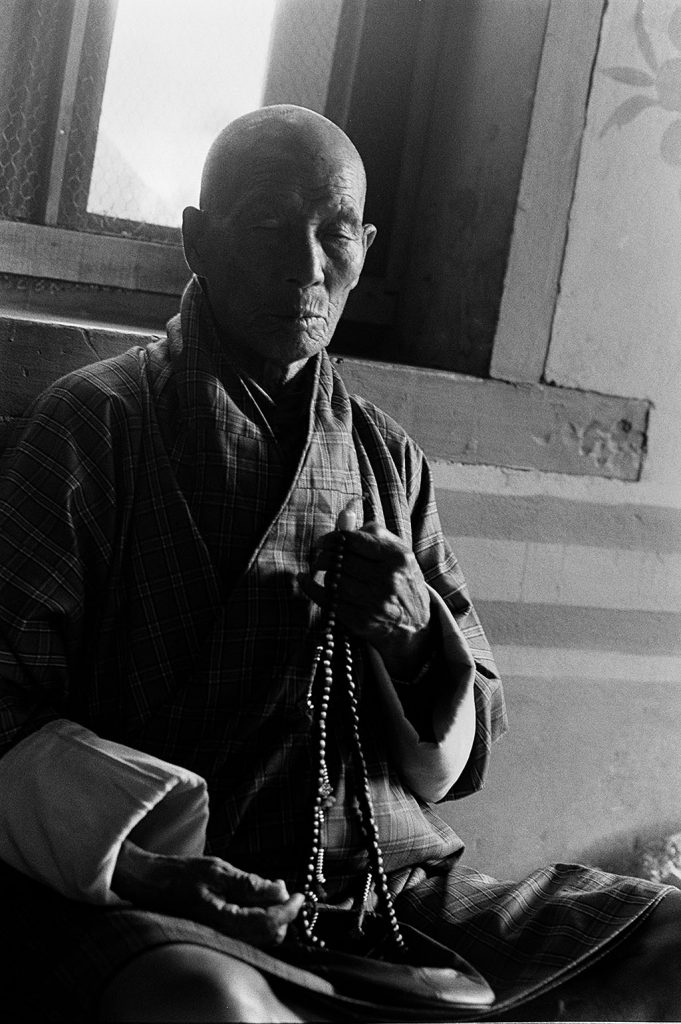

It was only a brief wordless encounter…but after seeing the image in print (much later, of course) I wished that I had taken the time to sit down and talk with him. This sometimes happens. When I’m behind the camera I focus on capturing the image. I rarely talk with my subjects, relying instead on non-verbal communication. In this instance, I have so many questions I would like to ask him.

This prayer house was part of a complex of several temples and gardens. The concept of a prayer house specifically for elderly people intrigued me. The atmosphere was quiet and the few worshipers there that day seemed to be deep in prayer or meditation. This atmosphere overtook me, too, and I took a few carefully composed frames, which is atypical for me. The result is a very intimate portrait, one in which the subject invited me to share the moment with him.

Here in the village of Khokana, I heard this man singing before I saw him. He and two friends were sitting on a low stone wall in the late afternoon, singing enthusiastically. He continued to sing even when I stopped to take this photograph. This was in late afternoon and that special sunlight just before sunset washed over his face and is reflected in the lenses of his glasses.

I would like to claim that it was my technique that captured such a moment, but serendipity played a role, too. For composition, there is a visual arc from his cap, to his face and then to his sweater, which makes the image more dynamic. It gives the impression that he was swaying with his music. I only had two frames left on the roll of film and later that evening I chided myself for not taking the time to reload and continue. I was shooting quickly, almost spontaneously, and this time luck was on my side.

Every afternoon, a Hindu priest leads a worship service there, which is characterized by the ringing of bells. Initially, one bell rings, then a second and third bell answers. Next, two or three bells ring in unison, and are echoed by other groups of two or three bells. The progression of bells grows – more and more bells in unison and answering one another at shorter and shorter intervals. All sizes and tones, from small bells with high timbre through larger and larger bells with deeper, more mellow timbre. Ultimately, all the bells ring together creating a cacophony of sound that is, nonetheless, spiritually moving.

When I went back the following year, I learned that this man had died. In a small way, it left me feeling that my task was unfinished. I wish I could have shown this photograph to him. It is a strong image, a haunting image. He had such an open face. I wonder what was behind those eyes.

Allow me to interpose one final transition. I’m going to end this episode of the Monochrome Chronicles by going back to two photographs from my early days with photography in NYC. Maybe returning to the beginning is an odd way to end the episode but this feels right to me. Photography has carried me great distances over the years – aesthetically, culturally, geographically and emotionally – but still I feel grounded by my early experience in NYC.

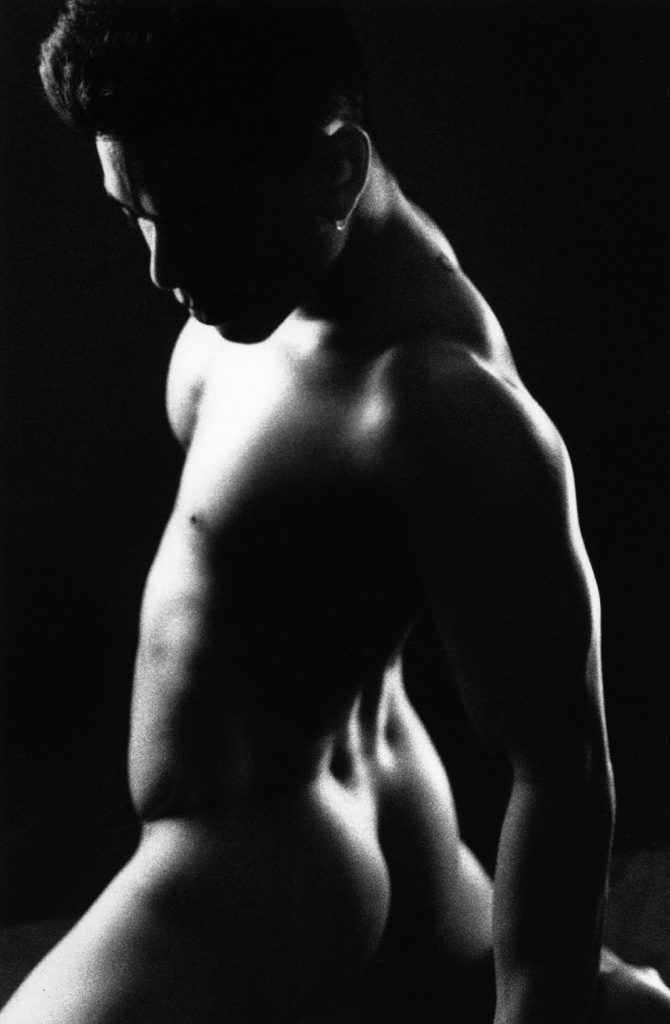

The male nude has been an ongoing theme throughout my 25 years behind the camera. This image is from my first series which I call the “black series.” Next came the “white series” and the “gray series” – not very profound titles, but they reflect where I was in photography.

At the time, I was still experimenting with exposure controls and lighting characteristics. Eventually, of course, the male nude became the medium. Sometimes I walked a fine line between the man as a model and the man as a subject, especially when photographing the same man over a prolonged period of time.

During the “black series” period, I developed a distinctive style: using ultra-high contrast and high grain film. The result was a series of photographs that reflect a thoughtful mood. This image is from my first series of make nudes, but the experience stimulated me to continue with and explore the genre. This man was both my model and my muse for over 15 years.

This has been my overview of the “Two Hundred Best” series. Clearly, the series covers a lot of territory in terms of subjects, in terms of time, and in terms of my experience. Funny, but I don’t have a clear recognition of how this series developed. By definition and according to my own criteria, the series has grown by annual installments over 25+ years. This is not the key element, however, which would be the content per se. It just now occurs to me that I was the only witness to the development of the series. I can only show you the final outcome – make that the current outcome.

My motivation for keeping the series is a bit difficult to explain. In a way, the series validates my experience of photography. As in, “I did this” or as in, “This is an expression of me.” Also, it has become a challenge. By definition, the quality of the series should improve every year as I add new and stronger photographs, and delete an equal number of weaker images. Finally, the series illustrates the breadth and depth of my experience in photography. For a while, the scope began to overwhelm me, but by limiting the series to a fixed number it seems more…more what? More fathomable, if that is a word.

A couple of observations emerge from this review of my “Two Hundred Best.” For one thing, the subjects vary widely. This is only to be expected considering the long period of time they cover. Naturally, my interest in subjects would wax and wane with time.

For another thing, the style of my photographs varies – usually with fine grain and sharp detail but sometimes coarse grain and less detail; usually casual but sometimes posed; sometimes shot from the hip and sometimes composed through my viewfinder. Some critics might cavil at these trends, accusing me of lacking consistency in my photographs. I would reply, “Not a problem. This is me. My point of view is kaleidoscopic. That is my style.”

In the introduction I wrote that the commonality of the photographs in this episode is that they all came from my camera. I should mention a couple of other commonalities. Each of the photographs is part of a series. And each of those series will be featured in future articles in The Monochrome Chronicles.